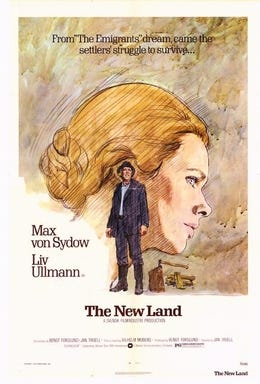

The Emigrants (1971) / The New Land (1972). Grade: A

Remember the lines from The Pogues’ “Thousands Are Sailing”? “Wherever we go, we celebrate / The land that makes us refugees / From fear of priests with empty plates / From guilt and weeping effigies.” This is that. A different home country, a different American destination, and a slightly different brand of oppressive piety. But the same feeling you get in that song.

These are based on a gigantic four-novel series by the Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg, who lived in America for several years (and visited Minnesota, where the books are primarily set). They’re directed, photographed, and edited by Jan Troell, and the way he manages to hold the sheer size of this together is an unbelievable achievement.

At the time, these were the most expensive films ever made in Sweden, so I imagine they had some financial assistance from the Swedish government. If so, kudos to the Swedish government; because Moberg and Troell sure make 19th-century Sweden seem like a lousy place to live.

Max von Sydow and Liv Ullman are struggling Rock Farmers in a tiny, provincial-minded Swedish village. OK, they don’t exactly farm rocks, but that appears to be the only crop which really does well there. Ullman’s family is tied to a splinter religious group that’s considered heretic by the local church bigwigs, and von Sydow’s more cheerful, younger brother keeps dreaming of how much better things supposedly are in America. So away they go.

The Atlantic crossing is as harrowing as you could imagine, and that’s when the story really begins to get its grip on you. Those ships were Not Large, and they carried a lot of people, and everyone had tight quarters with everyone else who was puking all over the place and eating the same horribly unappealing food. You’re quite aware that survival was largely a matter of blind luck and sticking through a miserable situation because there wasn’t any turning back. It’s an epic journey without any heroics.

Things don’t get any easier once they reach America, but you start to have a glimmer of hope that, occasionally, life might suck a little less for these characters. When they aren’t trying to keep feeble livestock alive in a blizzard, or almost losing children forever while changing boats, or nearly getting into a Civil War they don’t know much about, or dealing with neighbors going insane from the winters and Natives who aren’t very pleased about being pushed off their land.

This all sounds awfully grim. But Troell asbolutely avoids melodramatic message-sending, so it’s not grim to watch. You sure wouldn’t want to experience any of this, but you don’t want to miss the story. You want to see what happens to these people, who aren’t especially noble or especially wise. They’re just… interesting. (It helps that von Sydow and Ullman are outstanding actors with instantly fascinating faces.)

Pauline Kael, who I adore but whose ghost would probably find me boring, wrote that “American directors who love the outdoors usually love vast spaces … nature is used for beautiful backgrounds. Troell loves nature for itself — nature, weather, changes of light.” She writes that Swedish artists often have “earth spirit, earth poetry.” (That's a very unusual phrase for Kael, who usually barfed on anything vaguely touchy-feely.)

It's a great description of the cinematography here. Although I think Troell is doing something more basic and evocative than just earth poetry. He wants to show you the scope and feeling of this landscape because that's where the characters are stuck, now. It's big, beautiful, terrifying, and that's what they're facing. It beats farming rocks, but it's still daunting as shit. Troell gives you a sense of how tough it was for these characters, not to make them icons of anything, just to show them as people. Who they were.

There’s only one sequence, for me, that doesn’t quite work — when von Sydow’s brother lights off for the California gold rush, and gets utterly ruined in the process. Not that it’s a flaw in the story, at all, and Eddie Axberg, who plays the brother, is a fine performer. But the sequence falls into a kind of experimental-film nightmare presentation that’s very 1970s. Handheld cameras and surreal sounds to give you a sense of his misery.

That’s only about 10 minutes out of the whole six-and-a-half-hours; not a bad ratio! And, again, it does make sense for the story. Up until that point, these characters are desperately jumping into one risky undertaking after another, without ever being prepared for what they’re actually going to face, and having it (mostly) work out. Well, flirt with disaster often enough, and disaster can unfortunately get the hint. And it’s not because the brother is a fool; he’s a good man. Many good people fell prey to schemes that swindled them, in those days. Fortunately we’ve solved all of that, now.

In the very fine essay included with Criteron's discs, Terrence Rafferty writes that in the films, “marriage itself is a kind of emigration: a matter of settling into another life, making the necessary accommodations, and gradually—over years, over decades—finding that you think of this person who is not you, or this place that is not the land of your birth, as your home … [it] gives and it takes away, no blessing unmixed. The long married know that feeling better than most.”

Rafferty’s views on marriage may not be yours. But the love in a long marriage is the soul that carries these films, even if, in the end, von Sydow’s character gets more out of moving to America than Ullman’s.

There’s a nice statue in Sweden that depicts this, and depicts these characters. It shows the husband looking hopefully towards the future; while his wife wistfully glances back at the world, the extended family, she’s leaving behind — probably forever.

(I remember reading somewhere a modern American emigrant, from a very insular former community, saying the best thing about coming to America was that nobody cares what you do. And the worst thing was that nobody cares what you do. A rotten awful insular community which gossips if you're seen holding hands with someone they don't like is, in some ways, preferable to feeling without a community at all.)

Amusingly, there’s a lesser-quality copy of that statue in the small town of Lindstrom, Minnesota, which is popular with local tourists. The nearby, smaller town of Chisago City has a park named after Vilhelm Moberg. Small-town Minnesotans sure like to celebrate their hardscrabble foreign origins.

And the insular-minded region Moberg’s emigrants were escaping was called Småland.

Unless your family was very wealthy when they came to America, there’s probably some generation back in that history whose story was very like that of The Emigrants / The New Land. And if imagining that story laid out in a big, epic movie sounds at all interesting to you, DEFINITELY give these a try. (In order; The New Land won’t make sense without the first film.)

There’s another very fine, much shorter film about emigration to Minnesota called Sweet Land. But that’s challenging to watch in a different way, not because of the length. And maybe I’ll write about that some other day!1

I did! Right here. Although that review was done 10 years ago, so I might do it a bit differently, today. It’s not bad, though… and the last two sentences I’d definitely keep!