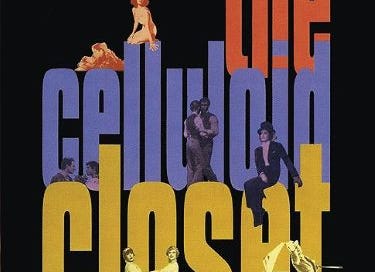

The Celluloid Closet

Solid, if too self-adulatory, documentary on Hollywood's depictions of gay folks in films.

The Celluloid Closet (1995). Grade: B-

This is a documentary about how homosexuality has been presented in movies from the pre-Code era to today. For many years, you couldn’t really show gay characters, not ones specifically identified as such. But there were ways to let savvy audiences know what was what.

If you remember The Maltese Falcon, put into your mind the scene where Peter Lorre comes into Humphrey Bogart’s detective agency. Bogart’s secretary (the terrific Lee Patrick) says Lorre’s been wearing a cologne (or is it perfume?) that smells like “gardenias.” Once inside, Lorre keeps fidgeting with his fancy walking cane. Like so:

Hmm, what do YOU think the prop placement means? That Lorre really craves cigars?

Before 1934, there were more obvious gay characters, although they were usually shown as such for a laugh. The best material shown in The Celluloid Closet are the clips from these early films, and I wished there was MUCH more of them. Like the silent movie clips Saul J. Turell compiled for his 1962 The Great Chase (really a fun watch, that one). However, the films Turell sampled were more popular when they came out, so there would be more copies in existence. And 1962 wasn’t as far removed from the silent era as this film is from the pre-Code years. So much of that material is certainly lost.

The clips have Lily Tomlin’s narration as necessary; when we’re not watching clips, we’re watching interviews with various movie personalities past and present. Actors, producers, screenwriters. (Plus Susie Bright, a feminist writer who once reviewed adult films for Penthouse.) As usual with talking heads, some are more interesting than others.1 I really enjoyed Jan Oxenberg, Quentin Crisp, Paul Rudnick (writer of In & Out), and Whoopi Goldberg — yes, the daytime-TV person, now. Hey, back then, she had one of the best Star Trek parts ever, she was fun. Bright is terrific, praising her favorite scenes in ways that makes you want to see them; and yes, the way Judith Anderson worships her dead boss’s underwear in Rebecca IS very wild.

Gore Vidal is, as always, Gore Vidal, with practiced anecdotes and barbs that sometimes really zing. Vidal says that when Hollywood wanted an outsider to oversee its self-imposed censorship rules, they looked to the famously corrupt Warren Harding’s cabinet, which “had some as-yet unindicted members,” and settled on Postmaster General Will Hays, who “resmbled Mickey Mouse.” Then the film cuts to footage of Hays — and, yep, he looks like Mickey Mouse.

There’s some interestingly different points of view expressed by Arthur Laurents (who wrote Rope) and Harvey Fierstein (Torch Song Trilogy), vis-a-vis the “sissies.” The characters, especially in pre-Code films, who were flamboyantly, over-the-top effeminate. (So long as homosexuals were presented as wimpy clowns, they weren’t threatening.) Laurents thinks those stereotypes were insulting, and compares them to the kind of Black stereotype Stepin Fechit played (the stage name of comic actor Lincoln Perry).

I kind of agree with him, and have always been bothered by those overtly-effiminate roles; the Jack character on Will & Grace, for example, played by Sean Hayes. But I knew gay people who thought Jack was hilarious. (And some Black audiences enjoyed Stepin Fetchit for fooling easily-duped White characters.) Harvey Fierstein thinks the old-movie “sissies” were hilarious, and says that’s because he’s a sissy himself. (Maybe so, but a sissy with a helluva butch voice!)

In moments like this, you wonder why the filmmakers didn’t interview John Waters, who can always be counted on to say something witty and observant about gay culture. (Although he’d probably have said somehing “shocking,” as well.) And it’s a pity this didn’t get financing until after the death of historian Vito Russo, whose book The Celluloid Closet inspired and informed the filmmakers here. When a documentary draws heavily on a book, the author is usually a really good source of interview material. Ken Burns and the American Experience documentary series do this a lot.

Russo died of AIDS-related complications in 1990, but the filmmakers had been talking to him before that. After his death, Lily Tomlin started a fundraiser and organized benefit performances in remembrance of Russo, with proceeds going to fund this project. They got financial assistance from the Paul Robeson Fund, too, which I’m sure he would have heartily approved of.

The directors are Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, who’d been making documentaries for several years, and are still doing good work today; their 2019 Linda Rondstadt documentary gave me new respect for that artist, and Epstein’s The Times of Harvey Milk should be shown in schools (in non-totalitarian counries, that is). They’re skilled hands at making this type of film.

But, I started to get a little bored with the film clips halfways through. Part of that is many of them are from visually ugly movies (most color movies in the 1950s looked bad), part of that is many of the clips are selected to illustrate things I already knew. Montgomery Clift was gay? Um, yes, R.E.M. had already done a song about that. Rock Hudson? Duh. Doris Day songs were often taken as gay camp? Quelle surprise! The Day song is cued up as Stephen Boyd and Chuck Heston exchange meaningful looks in Ben-Hur, and sure enough, Vidal tells his Ben-Hur story, which I enjoyed the first trillion times I heard/read him telling it.

Also, some of these clips feature just awful, awful acting. Vidal gushes over Boyd’s abilities; he’s more impressed than I am. There’s an extended bit using Suddenly, Last Summer which has Katherine Hepburn looking very interesting, and then Elizabeth Taylor just yowling all over the screen in that horrible way she’d do. Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause — ugh. And these are presented like they’re the GOOD moments.

Basically, the closer the clips got to today, the stronger the likelihood that either I was already very familiar with the movie, or it was a movie I had no interest in seeing any part of. Near the end, we see a good scene from Philadelphia, and a scene that epitomized everything which went wrong about that movie. It’s where Tom Hanks is looking quite sick, and talking to a doctor about his treatment options, and his partner Antonio Banderas doesn’t agree with the doctor. It makes a very strong case for why marriage rights shouldn’t just belong to straight people, as gay people’s partners deserve just as much say in their loved ones’ medical care. But the scene makes NO sense, because Hanks’s character agrees with the doctor’s opinion! Even if Hanks and Banderas WERE married, the doctor’s still gonna put the patient’s wishes ahead of the spouse’s. (That’s what the entire film did; it manufactured plot points to make an argument instead of having well-drawn characters driving the story.)

When the credits came up, I was looking for what hack composer to blame for this terrible, terrible score. I just assumed, from experience, that it’d be one of the Newman family. Uh-uh. It was Carter friggin’ Burwell. Carter Burwell! Who wrote the score for Miller’s Crossing and Fargo! The ONLY reason people like Fargo is because of that haunting, beautiful music! (Ok, there’s the excellent photography and some very good acting, too… but the music’s the biggest reason.) The score here, especially in the later sections, sounds like it should be run under footage of a hanglider soaring past golden-sunlit Italian coastal cliffsides. It’s far too majestic by half.

And I think that’s where this movie failed, a little. Its goal is to show how far Hollywood has come, how high-minded and wonderful its attitudes are, today. Holding up movies like Philadelphia (and showing quite a few others) as examples. Well, when Hollywood sets out to be daring, in a big bold way, the result is usually quite dang awful. It’s a system primarily designed to make money, occasionally trying to make money and “say something important” at the same time. Which is largely a crock o’crap. (There’s a super-brief clip from My Beautiful Laundrette, which is a far better movie featuring gay characters than most of the ones lauded here. Yeah, because Hollywood had nothing to do with it.)

Still, even some of these later clips have some good points to make. I have zero interest in watching Harry Hamlin in Making Love, but I enjoyed watching Hamlin TALK about making the film, and how his agent told him it’d ruin his career. (He was a big hit on L.A. Law, his career was fine — I really liked him on Mad Men.) And Tom Hanks has a great (sad) story about watching gay movie characters get treated violently when he was a teenager and cheering. Because, yep, that’s what teenage boys were trained to think back in those days (and in the years to come, I imagine). By society, by their peers, by parents. Everyone likes to claim they were totally open-minded from basically, birth, and only dumb bigots ever had any irrational prejudices. That’s ridiculous. You pick up attitudes as a kid and adolescent, and you learn to outgrow them. It’s a lifelong process.

So… I did like those OLD clips, and the people discussing how gay characters/situations were presented in the early Hays Code days. For example, how you could strongly hint that women were lesbians — but only if you made them Evil (like in Rebecca, or in prison movies). This is an honorable documentary, and there’s some good information here, especially for viewers unfamiliar with older films. It just starts dragging a little (and not in the fun feather-boa-wearing way). And it might give you an idea of some movies you’d like to check out, which is never a bad thing. I’d suggest other documentaries by the same filmmakers, though — the Harvey Milk one or Linda Ronstadt one. Milk, of course, was a good, brave man, and Ronstadt really is an interesting interview subject. Sure, she did marry George Lucas for awhile, but everybody’s made a foolish decision once or twice, now, haven’t we?

For example, I’d rather watch an interview with Tina Weymouth than one with David Byrne.