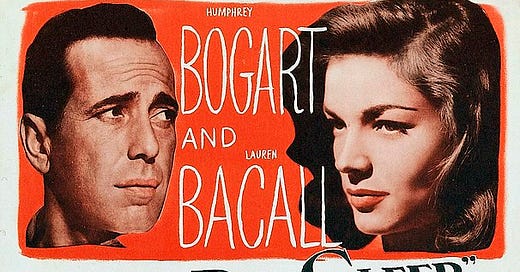

The Big Sleep (1945/1946). Grade: A-

One of those famous Hollywood stories, and in this case not as apocryphal as most, is about plot confusion on this set. The cast and director were unclear, in one scene, whether a character had been murdered (to cover up Dark Secrets) or killed themselves (to cover up Dark Secrets). Screenwriter Leigh Brackett wasn’t sure; she suggested sending a telegraph to Raymond Chandler, author of the original novel. Chandler wasn’t sure, either. Other screenwriter William Faulkner was probably off on a bender someplace.

Really, it didn’t matter. Keep shooting!

The plot, such as it is, involves Bogart being hired by a rich old degenerate to help resolve a small extortion; naturally, things get deeper and darker from there. The rich old degenerate’s teenage daughter does everything but throw her underpants at Bogart; the older daughter dislikes Bogart’s snarky irreverence. She’s played by Bacall, so you can imagine where this goes.

The novel, which I might/might not have read a zillion years ago, was like all other “hard-boiled” detective fiction of the time; depicting an urban world of wealth, perversion, and infinite corruption. So, rather like the “biblical epics” popular in Hollywood during the silent era, you could entice audiences by displaying all this fun, yummy immorality and also (kinda sorta) condemn it as Wrong.

And, boy, is there ever Wrongness on display! Bogart soon finds out that one of the blackmailers had the teenage daughter over, and gave her some kind of Loopy Juice, and has a hidden camera in the room — to catch robbers breaking in, I’m sure! To scope out the blackmailers’ bookstore front, Bogart goes into another bookstore across the street, and the INCREDIBLY GORGEOUS NERD CHICK working there points out that it’s raining, and inside three minutes she’s closed the store to… peruse the inventory, as it were. (I used to hang out in little bookstores all the time! Why did this never happen to me? Don’t answer, “duh, you’re not Bogart,” even though this is true.)

All these juicy perversions were apparently toned way down from the original book, and writers frequently put a lot more into screenplays than the puritanical Hays Office would allow; if you agreed to remove 5 Very Naughty Things, they wouldn’t always notice the 10 Subtly Naughty Things they’d missed.

(Sexy Cab Driver to Bogart: “call me if you can use me again, sometime.” Bogart: “Day or night?” Cab Driver: “Night’s better; I work during the day.”)

There’s quasi-illegal gambling and everyone’s scheming everyone and there’s plenty of murders, but mostly there’s just a lot of fun dialogue, courtesy of Brackett/Faulkner and expert joke-fluffer Jules Furthman. And, of course, Bogart/Bacall.

It wasn’t the first Bogart/Bacall movie; that was the equally senseless & enjoyable To Have And Have Not a year earlier. (In which Furthman and Faulkner completely threw out the original novel altogether.) By the time The Big Sleep came out, Have Not was a huge hit, and Big Sleep actually added a few extra Bogart/Bacall scenes after it’d been originally released!

Hence the 1945/1946 release date, above; this came out in 1945, some critics didn’t like it, so the filmmakers cut some dull bits and added more Bogart/Bacall bits and put it out again in 1946. Everyone loved it, and that’s the version which survived.

On the disc we got, which came out in 2000, you can watch both the 1946 and 1945 versions (on reverse sides of the DVD; a trend I hate that was used a lot at the time). There’s not much point in watching both versions. Hardcore film geeks can see a short presentation by a UCLA film archivist which explains the changes.

How is this, as a Cinema Film? It’s fine. There’s spots where the photography ain’t great. Some of the supporting cast are a lot of fun (always good to see Elisha Cook, Jr.), some are pretty hammy. The director, Howard Hawks, was a competent studio employee who could get a shoot done on time and on budget; there were a lot of these people around.

A fun bit of reading, for me, has been looking into the career of Leigh Brackett. She had written one pulpy detective novel titled No Good From A Corpse. Hawks had read in, and liked it; he asked his people to bring in “Mr. Brackett,” and was pretty surprised when a young lady walked in the office. But that wasn’t a big deal. As Brackett said in this neat 1976 interview, “the discrimination against women came in later, much later, when television came along with all these male-oriented western series and detective series, and they figured a woman wouldn’t be able to write that kind of thing.”

Brackett would work on more films, and she liked the money Hollywood offered, but she hated having to copy previous box-office hits. On one movie, El Dorado, her screenplay kept being tweaked to rip-off the earlier Rio Bravo — which Brackett also wrote! She told star John Wayne, “you did that scene. I’m not going to write those lines again.” And “‘Duke looked down at me from about eight feet high and said, “That’s right. If it was good once… it’ll be just as good again.’”

What Brackett really loved was writing “planetary romances,” or what we’d call “space operas,” or “soft science fiction.” (As opposed to “hard science fiction,” which will have some tedious description of how quantum wormholes could work.) Andrew Liptak wrote a brief, admiring overview of her sci-fi with this fun information:

“‘Her mother and relatives weren’t supportive of her interest in science fiction, or her writing in the genre. An aunt once asked her: “Why don’t you write nice stories for the Ladies’ Home Journal?”, to which Brackett replied: “I wish I could, because they pay very well, but I can’t read the Ladies’ Home Journal, and I’m sure I couldn’t write for it.”’

Charlie Jane Anders wrote the article which led me to that one and the 1976 interview. And there’s additional fun for Star Wars fans. George Lucas, a fan of Brackett’s sci-fi, brought her in to write a draft of The Empire Strikes Back. Most of it was rewritten by others later, but in Brackett’s version, the love triangle plays out separately from Luke’s twin sister, who we’d meet in the final film. Tell me that’s not a lot better than what ended up onscreen!

Oh, and Brackett also wrote another Raymond Chandler adaptation… which film buffs will know as Robert Altman’s wonderful The Long Goodbye. (Although, with any Altman movie, how much of the original script made it into the final film is very debatable…)

Check out that 1976 interview if you like, it’s fun. And has Brackett’s husband Edmond Hamilton in it, also a writer. They tried collaborating, once. And almost broke up because of it. They stopped trying that, and had a long, happy marriage.1

Even if you aren’t interested in that sort of thing, I enjoyed learning about Brackett as that rarest of writers; somebody who did what she wanted to, didn’t worry what others thought, and managed to make a pretty decent living doing so. That’s darn good, folks; especially for anyone who’d ever hung around Hollywood.

And if you’ve never seen it, go get The Big Sleep already! I promise you’ll have a great time. Just don’t worry if you can’t quite follow the plot. Nobody else did, either.

Fans of old sci-fi will be interested to read about Hamilton’s experiences with big-time publisher John C. Campbell, who was a bit of a controlling jerk.

I've seen the original edit. One of the boring scenes (the main one) that was cut has Bogart explaining the plot. The scene goes on a while. The thing is, the plot still isn't clear even with it. The release print has a lot more flirting with the two principals and it is a lot more fun.

The bookstore scene is hilarious with the "Why Miss Malone, you're beautiful!" bit. The actor is Dorothy Malone who, if you ask me, is a good deal prettier than Bacall -- especially with her hair back and wearing glasses. When Bogart asks her to remove her glasses, all I can think is that he's gay. I've known a few gay guys who, before coming out, were ridiculously critical of female looks.

Brackett is impressive. I think The Long Goodbye would have been better if they had stuck closer to the script. The scenes that seem most improvised are also the worst scenes in the film. Also, I assume the ending is her's since the entire film leads to it. And it is totally different from the book.

I think Howard Hawks was a great director. But these kinds of directors (Michael Curtiz is another) don't tend to get their due. Or rather, other directors who are roughly the same today are worshipped as geniuses when they largely just do a job well.

Anyway, I like this film. It's fun. But The Maltese Falcon is way better!

Oh, I do really like Cook playing a sweet guy.