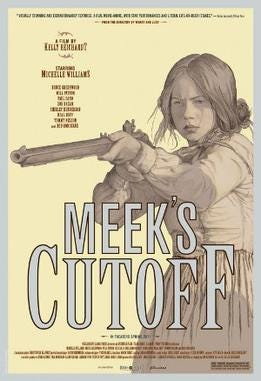

Meek's Cutoff

Intentionally difficult and frequently brilliant film about how being an Old West pioneer woman basically stunk.

Meek’s Cutoff (2010). Grade: B+

This is gonna be a different movie rec than some of the ones I’ve given. When I’ve suggested a difficult film before, it’s difficult because the subject matter is depressing, or the film contains material that’s very disturbing to watch. Well, here the subject matter’s depressing, but there’s nothing hugely violent or too harsh to look at. It’s rated PG for a few mild words and there is some meanness on display; there’s no blood or gore. Nobody dies of dysentery (unlike in the 1985 Apple II+ educational computer game).

This is a difficult film because director/co-writer Kelly Reichardt intends it to be. It’s got a lot of slow-paced sequences with virtually no dialogue. The lighting is deliberately quite low in spots. And the ending doesn’t resolve anything.

I think it’s brilliant; I think Reichardt might be the most interesting American filmmaker today. But this movie is NOT going to be for everyone’s tastes. Other films by her are easier to get through, like Certain Women and Night Moves.

This is loosely based — you might say isnpired by — a true story. (Told very well by Danielle Denham here.)1 On one of the last stages along the Oregon Trail, a conventional route was to go northwest from the Snake River to the Columbia. That meant crossing the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon. Following roughly the route used by I-84 today. Here’s part of Wiki’s map:

The diagonal brownish line to the east is I-84. The little mountain symbol is where the Blue Mountains are.

The Blue Mountains aren’t as high as the Rockies, but the route through them was extremely rugged, and by that point in the trip, a tough slog for humans and livestock alike. We were taught as children in Oregon that so many items were dumped from wagons while crossing the Blues, one could follow the basic path of the trail just by following the cherished keepsakes discarded on the way. (And there’s a scene similar to this in the film.)

In 1845, experienced mountain man Stephen Meek led one set of settlers along a different route, bypassing the Blues entirely; there had also been some rumors about possible attacks in the area from angry, encroached Native tribes.

Meek’s route was heading west from the Snake River (on what’s now the Idaho border) to the Deschutes (a north/south river that empties into the Columbia about 100 miles east of what would become Portland). That’s longer overland, but theoretically less difficult. About 200 families decided to follow Meek’s direction.

And then he got them very definitely lost.

The main problem was, Meek had planned to follw a route going from creek to creek and lake to lake. But it was a drought year; many of these were dried up. So the caravan was lost in the Oregon high desert, and running out of water & food. It didn’t end up a Donner Party situation, nobody ate anybody, but about a quarter of the settlers died. Some who’d lost family members wanted to murder Meek — he and his wife were saved by Natives who helped them escape.

This is mostly all changed for the movie. There’s only three families following Meek’s route, and Meek isn’t with his wife. The one Native they encounter is definitely not eager to assist. These changes aren’t made to butcher the real story; they’re made to express something different than a straight-up narrative. Reichardt isn’t making a historical drama; she’s trying to show what a total acid bath slogging through the desert must have felt like.

The first shot has wagons and oxen fording a river; we also see women crossing separately, carrying items they don’t want to get wet, like clothing and a birdcage. Everyone’s too weary to make conversation. Soon after this, we watch one young man carving an inscription on a piece of wood: “LOST.”

The men make their decisions a distance away from the women, perhaps not wanting to “distress” them about what a bad situation they’re all in. But the women definitely have figured it out, duh. Everyone’s getting irritated with everyone else; two of the women (Shirley Henderson and Zoe Kazan) are starting to completely break down. Only one of the whole party (Michelle Williams) appears to be thinking clearly; even so, she hates every single thing about this unholy mess.

(Williams you probably know; Kazan, possibly, and if you haven’t seen her in The Big Sick, go do that! Henderson may not look familiar, but you might recognize her voice; she was Moaning Myrtle in the early Harry Potter movies.)

The three husbands are simple-going Neal Huff, calculating Will Patton, and pushover Paul Dano (Kazan’s husband in real life). Meek is played by the fine and frequently under-used actor Bruce Greenwood. His Meek is cheerful bluster at first, telling the one boy on the journey about his amazing wilderness exploits. What should you do when you’ve mistakenly led people into a possibly hopeless situation? Tell them how hopeless it is? Or try to stay optimistic for the good of the group?

Later on, Meek’s confidence starts to waver — the men are seeing him for what he is, the type of person who claims to know more than everyone about everything because they’re in way over their heads. (The women more-or-less suspected this about Meek from the start.) Meek becomes angrier, more insulting, more rigid.

The excellent cinematography’s by Christopher Blauvelt; and he’s shot all of Reichardt’s susbsequent films. It gets the look and colors of Oregon’s high desert down perfectly, with sharp, vivid images. (Even in this bleak landscape, there’s touches of beauty like a spiderweb glistening in the sun.) It’s shot in 4:3 ratio, which means it will be a box-like image on your widescreen TV — just like almost everything before 1953, so it shouldn’t bother you.

What’s more difficult, visually, are the night scenes. Reichardt and Blauvelt choose to film these scenes in mostly very low light, only illuminating the actors from weak lanterns and small campfires. It’s not really like any night shots you’ve seen before — it’s dark, like the outdoors actually is when you’re camping. If you watch this anywhere near a daytime window or in a bright room, you will NOT be able to see what’s going on in these scenes. And they’re important to the story; they show how the women express their doubts individually to their husbands, and the husbands share with their wives only part of the whole picture.

Eventually, the party is “joined” by Rod Rondeaux (he’s a Native actor from Montana). He is not thrilled about being there and not interested in responding to English. (Some of the tired, terrified settlers just speak English words louder to Rondeaux as if he’s hard of hearing.) Is Rondeaux against the travelers or stuck/forced into the same bad situation they are? He’s not going to tell them, or us. (Nina Shen Rastogi translated Rondeaux’s dialogue into English; you can read that here, although don’t do so if you don’t want to know plot points in advance.)

Besides the slow pacing and limited amount of dialogue — neither of which bother me at all, although they will bother some viewers — there’s two flaws with the film. Neither are important. One is that the dialogue is trying to sound like diaries from the period, and this doesn’t always work; it didn’t always work on Deadwood, either, or in “The Gal Who Got Rattled,” the longest (and best) segment of the Coens’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs. (Which also has Zoe Kazan in it.)

Two is when there’s a late, rather predictable story moment; that’s set up and you’re waiting for it and then it happens. It’s the one time the film doess anything of this sort; most of the story seems to happen without any forewarning, like it really would in an unpredictable situation. (Unpredictable except for things continuing to get more dire, but everyone in the caravan’s aware that’s gonna happen.) The story moment pushes the plot to its climax, so I see why it’s in there; but it’s the one obvious moment in the film. It stands out as feeling more forced than the rest.

Again, those aren’t major. What may majorly frustrate some viewers here (it drove Mrs. twinsbrewer crazy) is that the film, simply, ends; the eventual fate of everyone slogging it through the desert is left a mystery. I have no issue with that, especially now that I know it’s coming. This isn’t an adventure story; it’s not a survival story; it’s not meant to teach you specific history. It’s meant to get you thinking about what these exhausting journeys were actually like for a lot of people. The grand, gorgeous vistas of, say, a Sergio Leone western are largely shot in places where nobody could actually live, there’s not enough water!

I remember one time visiting some remote park and seeing a old, old settler cabin, long since abandoned and slowly falling apart. Near a pathetic little fetid pond. The cabin’s well over 100 years old. A park sign indicated that it’d been the home of some lonely settler, far from anyone else; his young wife had died soon after they moved there. That sort of thing makes you wonder what existence was like for the wife; Meek’s Cutoff tries a little to answer just that kind of question.

Incidentally, while most critical reception to this was OK-to-grudugingly admiring, one critic who positively HATED the thing was Quentin Tarantino! Probably the pace of it drove him nuts. Although another film on his “hated” list from that year was the perfectly straightforward and friendly Potiche, where Catherine Deneueve plays a widow who inherits her husband’s factory and promptly begins running it better/less snobbishly than he had. Maybe he just doesn’t like these kinds of gals-being-less-clueless-than-the-men stories? Or expected somehing different from this one, more likely.

Go into this without expectations of what a Western, period movie should be, and it might surprise you. You likely won't enjoy it, exactly; but it might be something that makes an considerable impact for you. It did me. And if it doesn't, your library copy was free!

By the way, there’s an excellent modern-day nonfiction book, The Oregon Trail, by Rinker Buck. It’s about Buck and his brother attempting to recreate the original Oregon Trail wagon journeys in a wagon of their own; the two brothers have very different personalities. It’s a lot of fun and has interesting wagon travel/animal lore! Like, mules aren’t stubborn because they’re grouchy — they’re stubborn if they smell predators in the distance, because they have AMAZING senses of smell. (So do dogs, but you can’t hitch a wagon to dogs). Worth checking out!

Denham seems to do the type of writing any sane person would love to do. She travels around Oregon writing about fun local attractions and historical oddities, taking pictures as she goes. Here’s some neat photos of old abandoned farmhouses she took for a book she’s working on. Very cool stuff.