Drugstore Cowboy (1989). Grade: B

If you took the Cheech & Chong characters from Up in Smoke and got them addicted to opioids, you might wind up with something like the characters in Drugstore Cowboy. People with one goal in life; to enjoy being high and plan their next way of getting high. Except that smoking a joint the size of a hotdog won’t kill you, and opiods certainly can.

Jon Raymond’s interesting, slightly overpoetic Criterion essay points out that the title here (from a then-unpublished book by then-prison inmate James Fogle) suggests Midnight Cowboy and Urban Cowboy, stories about modern disillusionment. It also suggests the romantic myth of the “cowboy” as told in country music songs. Those fellers who’re at their happiest among other cowboys, roamin’ the lonesome prairie, needin’ nothing but a guitar and a campfire and a can o’ beans. These addicts, always adrift, always rootless, don’t even need the can o’ beans. Just the junk, please.

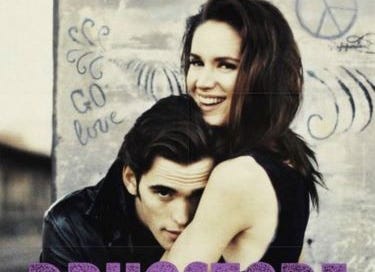

Matt Dillon leads a “crew” of four; just himself, his wife Kelly Lynch, their protege James LeGros, and his “woman,” Heather Graham. The earliest scenes establish their routine. Lynch/LeGros/Graham create a distraction in a drugstore, this draws the attention of the phramacists, and Dillon then ransacks the pharmacy for pills. (He grabs bottles at random and sorts them out later, discarding useless ones like stool softeners.) Then they all make their getaway, go back to their flat, and get high. Until they run out of drugs. Then it’s back to ransacking drugstores.

Dillon and Lynch do love each other, in a way. They just love the junkie lifestyle more. So much more that when, eventually, one of them announces an intention to get clean, the other takes it as a major insult. (Like announcing you’ve been having an affair.) The way Dillon plays it here, he’s a resigned romantic. He knows he’ll probably lose her someday. He merely wishes it didn’t have to be that way.

Looking back on the movie 25 years later, director/co-writer Gus Van Sant said he had originally wanted Tom Waits for the Dillon part, and Waits was interested; it didn’t happen because of what the production company and various talent agents decreed. Van Sant wanted Waits because, well, Tom Waits is cool. And closer to the age of the character as written. Waits has been fine in various Jim Jarmusch movies, and was quite good in the “All Gold Canyon” segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs; I’m sure he’d have done a good job here.

But it would have cost the movie its greatest strength, or at least what I see as its greatest strength 35 years later. How young everyone seems. (Especially in the “home movie” footage that opens and closes the film.) I’m very aware that I’m 35 years older than when I saw this. And what I see are young people utterly wasting their youth.

Now, someone who likes the junkie lifestyle wouldn’t consider it wasted at all. And that’s fine, for them. But when I see Lynch climbing all over Dillon and begging him to make love to her, and him being too high to be interested, I think, “kid, you’re not gonna be in your 20s forever.” (Dillon was 25 when this came out; Lynch was 30, and Waits 39.)

Dillon had already appeared in quite a few films, particularly the adaptations of S.E. Hinton’s young adult novels (which I did read as a 13 year old and found very moving, so I’d be ashamed to look at them now). This movie got him some parts in more commercial projects, but for most of his career he’s worked in independent film. He’s got the ability to play someone who’s a little dazed without seeming actually dim. Drugs have slowed his character’s reaction time, here, yet he’s quick-thinking when he needs to be. And when Dillon plays sad, it’s not mopey; it’s wistful.

The rest of the “crew” are fine, as well; Kelly Lynch (no relation to director David), who’d later work a lot in television, and Heather Graham, who’d be quite the “in girl” for several years and seems to have enjoyed most of it. Lynch seems a little too phony and Graham a little too ditzy, but that’s their characters. James LeGros is really very good as the dopey henchman, without seeming like he’s acting at all. He has a brilliant bit where he tries to throw a punch. And a terrific IMDb bio line: “It isn't hard to make James Le Gros bust a gut laughing. Just call him Brad Pitt.” (He’s been called the “Brad Pitt of independent movies,” and apparently once played a character that was a kind of Pitt parody.)

Incidentally, for my fellow Minnesotans: LeGros is from Minneapolis, Lynch from Golden Valley, and Graham from Milwaukee, for what that’s worth.

Before moving to Minnesota, l grew up in/around Portland, OR, where this is (mostly) set and filmed. And as a teenager/young adult, director Gus Van Sant was really my hero. I wanted to be like him, and become a respected indie filmmaker. I saw My Own Private Idaho when I was in L.A. attending (and hating) film school; it made me want to go back to Portland and make an independent film, like Van Sant had with Mala Noche (a heartfelt, low-budget work that got Drugstore Cowboy financed). I even spent $20,000 making such a film. The difference was, Van Sant’s movie was good and mine was crap; it probably helped that he was a mature adult and I very much wasn’t.

I so identified Van Sant with indie filmmaking and underdog Portland that it felt like a betrayal, a personal insult, for him to make To Die For outside of Portland and with Nicole Kidman. I walked out of the theater after 15 minutes. (I still haven’t seen the rest, although that’s because of Kidman, not Van Sant.) Now of course, I have no particular feeling about any directors as heroes, or care about Portland’s “underdog” status (it used to be Seattle’s little brother, that doesn’t seem to be the case anymore). I don’t know if I’d recognize anything in the city anymore, I haven’t been there for 20 years. An interesting site that looked up Portland locations from Drugstore Cowboy decades later found that almost everything that hadn’t been torn down had been converted into condos. (And in fact, the conversion of Portland into a hipster city was one reason I left.)

I’ve seen some of Van Sant’s later films, and liked some of them. I should check out his littler, independent projects, as he seems to make Hollywood films to finance the indie ones. I did enjoy aspects of Good Will Hunting (the acting’s better than the so-so-script), and admired Milk all-around. (An interesting undercurrent to Milk is that Josh Brolin, who plays the murderous homophobe Dan White, wore the same haircut Van Sant had in the 80s/90s, and was the same haircut the actual Dan White had in the 70s/80s; the movie has a lot of sympathy for his awful character.)

Oddly, my favorite indie filmmaker now, probably my favorite filmmaker period, is Kelly Reichardt, whose movies usually take place in Oregon (although her best, Certain Women, is set in Montana — and it has James LeGros in a small role). That Jon Raymond who wrote the Drugstore Cowboy Criterion essay? He co-wrote six of Reichardt’s films. (All very good; I liked Meek’s Cutoff, Night Moves, and Old Joy the most.) While I probably first checked out their work because Wendy and Lucy was set in Portland, that wasn’t why I admired the movie, though. I just like Reichardt’s filmmaking eye and the way she treats her characters. I’d have liked Wendy and Lucy if it was set in Minneapolis or Memphis. The same goes for Drugstore Cowboy, too (at least now, it does).

It was a hoot seeing William S. Burroughs in this after watching Daniel Craig playing Burroughs (and doing a decent job of it) in the empty, pretentious Queer. The real Burroughs is funnier in five seconds than the lousy script and direction of Queer ever accomplish, intoning “there is no demand in the priesthood for elderly drug addicts” in that singular Burroughs way. The scenes were shot in one day, and Burroughs’s lines are all written by his editor/personal assistant, James Grauerholtz, in the Burroughs “style.”

There’s decent parts for Max Perlich as a really dumb, really mean drug dealer, and James Remar as a cop who routinely harassess Dillon and his crew; Remar’s the closest thing this movie has to too hammy at times, although he’s quite likeable in the end. Grace Zabriskie is memorable, as always. And a neat tiny part for Beah Richards as a drug counselor; her face looks so familiar, I wondered if she was a politician or something like that doing a cameo. (No, she was an actor, but she was in movies and TV for 40 years, so no wonder she looked familiar.)

This isn’t, quite, a great movie, since its scope is so limited. It’s a bit like a druggie version of California Split, which was about compulsive gamblers; Jon Taylor notes that the Dillon character believes in hot streaks and cold spells the way a gambler does. California Split was about one character realizing that the highs weren’t worth the rootlessness anymore, and so is this. But even if the movie isn’t “great,” it’s nearly perfect at doing what it sets out to do, and doing so without any hint of judgementalism towards its characters. They’re not hip for being on drugs and not evil for being on drugs. They’re just on drugs.

One of my favorite parts in 1989, and in watching it now, is a short little musical interlude about halfway through. (Just like my two favorite moments in Private Idaho were set to music.) It comes as the crew is traveling the Northwest, staying one step ahead of the law (and finding whole new drugstores to steal from). It’s set to a 1968 reggae song, “Israelites,” by Desmond Dekker & The Aces, and was one of the first Jamaican reggae songs to receive international attention. The song’s in Jamaican Patois, and some of the lyrics are tough for outsiders like me to understand. Which is featured in this 1989 Maxell cassette tape ad:

Cute! But you should listen to the full original.