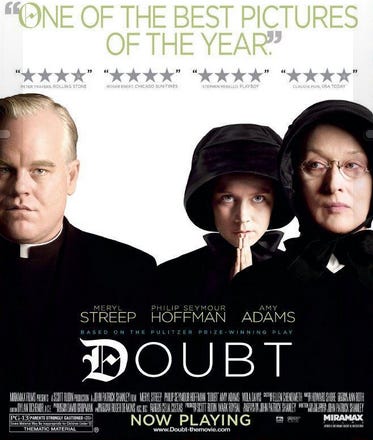

Doubt

Incredible cast in John Patrick Shanley's powerful film about "maybe."

Doubt (2008). Grade: B

The priest tells a story, about a lady giving confession. (It’s a fictional story; Catholic priests do not reveal what’s been said in confession.) The lady said she’s been guilty of the sin of gossip. What should be her penance? (Penance is a task the priest assigns to make you think about your transgression.)

The priest says, go to your rooftop, and cut open a feather pillow. The lady does, and returns to confession. Then the priest tells her to go gather every last feather from the pillow, and put them all back. The lady replies, that’s impossible! The feathers were scattered by the wind!

And THAT, says the priest, is gossip.

(As you’d imagine, Philip Seymour Hoffman tells the story more compellingly than I do.)

Hoffman plays an easygoing priest assigned to a Catholic school and its church (many Catholic schools have a church, too — the school charges tuition, but attending Mass is free to all). It’s 1964, so, this is during the period of Vatican II. (A series of reforms in Church practices which aimed to make the message of faith more accessible to everyone.)

These reforms were highly controversial within Church circles at the time. (Among far-right Catholics, they still are.) Hoffman’s a supporter of the reforms. Meryl Streep, as the nun who runs the school and its teachers, is definitely NOT. These two were bound to butt heads, no matter what.

Then, one day, idealistic young nun/teacher Amy Adams tells Streep about something she saw. A kid (the school’s only Black student, it’s an Irish/Italian neighborhood) comes back from a meeting with Hoffman, looking distressed. And Adams smells alcohol on his breath.

Well, Streep deduces what’s going on, for sure. She concludes that Hoffman got the student drunk to take advantage of him, to sexually abuse the kid. How does she know? Because it’s happened before, with other priests. Everyone knows this. Even Adams knows this, and she’s only been a nun for a few years.

The movie’s based on a play that was first staged in 2004, by John Patrick Shanley (Moonstruck, Joe Versus the Volcano). Shanley also adapted and directed the movie version. The Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigation on sexual abuse in the Catholic Church was printed in 2002. Certainly, the subject was a matter of public outrage and debate when the play debuted. It might have been a matter discussed among some Catholics long before that.

I grew up Catholic, but stopped attending Mass when I went to college in 1990. Not because I knew of anything awful going on with the Church, but simply because I wasn’t sure I believed in its teachings, anymore, and it felt hypocritical to pretend I did. After the widespread abuse scandal became public, I had some discussions with my Mom about the subject. She’d taught classes about the faith for years to teenagers at her church, and continued to do so until she became too ill. I asked, was this something that adults in the Church had talked about, but kept from us kids?

She said, there had always been rumors. But these were mostly speculation. When priests were reassigned from one church to another, there were always reasonable-sounding explanations given. If it was an older priest, it was because the congregation needed to remember their faith was in the Church itself, not just one well-liked individual. If it was a younger priest, it was said that he was being transferred to replace an older priest who died or became too frail to continue. No doubt some of these explanations were true. No doubt some weren't.

Hoffman’s young-ish priest is great at relating to the kids (he also coaches the basketball team). And just the sort of priest I'd have liked at those kids’ age — he listens to their concerns and responds with humor. The Amy Adams character sees this as admirable, as something she’d like to do with her students, too. But Streep sees it as proof of his depravity. Anyone who’s nice to children is, by default, not to be trusted.

The movie’s about the battle of wills between Streep and Hoffman, but it’s also about the battle going on in Adams’s mind. About keeping her idealism or seeing it as naive. After all, when she tells her class to settle down during a giggling fit, the kids don’t always listen to her. When Streep comes in the room (she’s the school principal), those kids sit up and shut up. They’re terrified of her. (Adams and Hoffman share a private joke early on when they see Streep taking a kid to her office; “the dragon is hungry.”)

Streep gives Adams a useful pointer; make sure you’ve got a glass-paned picture of the Pope right next to the chalkboard. That way you can see the reflection in the glass, of kids whispering or passing notes. They’ll think you’ve got eyes in the back of your head. And Adams tries this, and it works. Maybe Streep’s right about how to treat the kids, after all…

It’s an old question for people with any kind of authority, or power over others. I remember being told, at one job, that “you’ve gotta be willing to put them on the ground, so that they know you’re not afraid of them. Or else they’ll walk all over you.”

(What job was that, pray tell? Prison guard? Riot police? Nope… it was providing services to persons with cognitive/communicative challenges, such as autism or schizophrenia. And this facility was considered one of the LEADING facilities providing such services. Almost all the parents of the residents were humongously rich. That’s the kind of training they were paying for.)

And that’s one of the subtle dynamics in the Streep/Hoffman battle, too. Sure, he wants the Church to reform, to be kinder and more caring to kids in the schools, to adults in the congregation. But he’ll also rely on his authority when he has to. Because, after all, it doesn’t matter how long Streep’s been at this particular school, how relatively new he is. He’s also a priest. And priests outrank nuns, that is that. And he’ll use it. (We see the priests at dinner being allowed to drink and smoke and tell jokes — no such luck for the nuns.)

The movie’s meant to keep you in the dark about what actually happened between Hoffman and the student. He gives a plausible-sounding, innocent explanation. Adams — mostly — believes him. Streep won’t, because he’s a reformer, and they’re all untrustworthy.

Shanley has said that you’re not supposed to know. He says HE knows what happened between the priest and the boy, but he’s not going to tell us. He told the Broadway actor… but he later said he’d been sneaky about it. He told Hoffman… but he’s not sure Hoffman played it the way Shanley told him to play it. (And still called Hoffman’s performance “brilliant,” which it is.)

The situation’s complicated by the arrival of Viola Davis a little more than halfway through the movie — she’s the kid’s mom, and was asked to come in for Streep to tell her about her suspicions. Davis explains that her son is being badly abused at home, and that having a concerned adult who cares about him — as Hoffman clearly does — is vitally important to the boy right now. She’ll take that, no matter what else might come along with it. And since the kid hasn’t told her about anything happening, and she’s not going to pull her son out of the school — then why is Streep still pestering her? What’s the point? (It’s a helluva scene, with the same kind of energy that Kathy Bates packs into her “I’m done with your bulls**t now” parts.)

It surprised me to learn that Shanley was also thinking about the buildup to the invasion of Iraq — how the administration decided to say that weapons of mass destruction did exist, whether they could show any evidence or not.1 And no matter what conclusions you draw from the movie, it’s obvious that the point is about how stubborn assurance is a dangerous thing.

The critic Pauline Kael used to say that Meryl Streep had a tendency to hide behind accents. And it is jarring when everyone else just seems to be talking in their normal way, yet when Streep opens her mouth, it’s a heavy Boston/Brooklyn accent (although, for all I know, that’s the way the character’s written). But I’ve come to accept Streep’s accents the way I accept how some actors just like performing behind false noses or with wigs. It it helps them, it helps them. And you certainly believe in the character, who sees omens in burnt out light bulbs and rants about Frosty the Snowman’s pernicious influence.

One of the best scenes — and there’s several to pick from — is when Hoffman’s sitting with Adams, both talking about their commitment, him to the congregation, hers to her students. Hoffman tells her, “There are people who go after your humanity, Sister, that tell you that the light in your heart is a weakness. Don't believe it. It's an old tactic of cruel people to kill kindness in the name of virtue.”

It’s a powerful moment, both for the pain on Hoffman’s face as he says it, and the truth of what he’s saying. And knowing that right-wing backlash against Vatican II would lead to a powerful strain of American Catholicism; that the Streep character’s side would, largely, win. Don’t think that’s relevant to you, because you might not be Catholic? Well, there’s six super-conservative Catholics on the U.S. Supreme Court today. Quite definitely cruel people who kill kindness in the name of virtue.

Beyond the excellent performances and the quality script, Shanley does a decent, no-frills job of direction. He has the good sense to hire expert cinematographer Roger Deakins to take care of the images, so he can focus on the performances, instead. Howard Shore has written good, subtle music for movies before, and some big, bombastic scores as well — this is one of his subtler ones. (He also did the music for High Fidelity — why did that movie even NEED a composed musical score? Everyone just remembers the songs, for pete’s sakes.)

I don’t mind the ambiguity of “what did the priest do” at the end — it doesn’t leave you hanging, it just lets you form your own opinion. I have mine, and the director of the original stage production had his.2 But I do mind that we don’t get, quite, a resolution of the conflict in Adams’s thinking about teaching, the one between her idealism and Streep’s strict concept of authority. There is, a little bit, where she snaps at a kid, then sincerely apologizes. But I did want her to completely reject Streep’s methods a little more. I’m not the writer, though, it’s not my character to create.

If you don’t see this for any other reason, see it because it’s one of the very best performances by an actor who gave so many great ones, and who died far too soon. Mrs. twinsbrewer wondered what Philip Seymour Hoffman would be like if he were still with us, today. It’s hard to say. But I imagine he’d still be a deeply troubled man. Yet one who was still a phenomenal actor.

Since the whole point of having weapons of mass destruction is for everybody else to know that you have them, you rather wish more of the media had called the administration out on this. They didn’t.

That director said he thinks the priest was 100% innocent in the matter of the young Black student, and hasn’t touched any kids at his new post. But that he had in the past.

I prefer to think that the priest is gay. And that his bond with the boy is in telling him it’s OK to be what he is (the Davis scene with Streep tells us the boy is gay). But that the priest’s been caught having sex with adult men, and it’s gotten him transferred before. There’s nothing in the movie to indicate this, except maybe the way Hoffman answers a question about dancing with girls to one of the students. It’s just the way I choose to see it. Which is as valid as any other way. Unless I’m completely wrong, which wouldn’t be the first time.