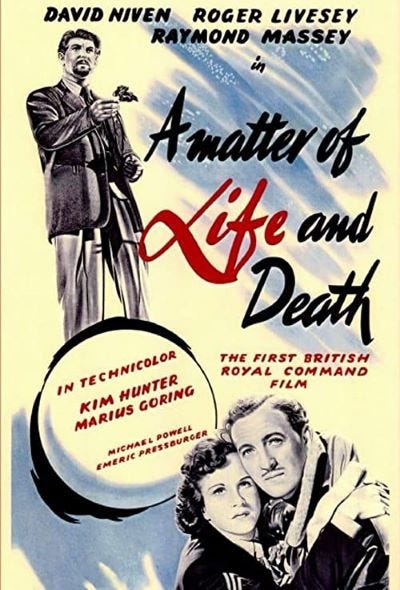

A Matter of Life and Death

Reasonably enjoyable but EXTREMELY confused film with some neat effects work.

A Matter of Life and Death (1946). Grade: C+

David Niven’s RAF plane is on fire and going down. The only remaining parachute is shot up all to heck. He’s going to jump out and fall to death rather than burn to death.

Before jumping, though, he has one final conversation with a radio operator, a nice-sounding American lady from an airbase in England. It’s his last chance to hear a human voice, and to have someone feel sad for him before he dies — wouldn’t you? They have an emotional conversation for a few minutes, then he jumps…

…and wakes up on a beach, unhurt. At first he thinks it’s heaven. But no! It’s near the airbase! Somehow he survived! And now he meets the radio lady!

Well, somebody in heaven made a mistake. He was SUPPOSED to die. But the heavenly “Conductor” supposed to retrieve his soul couldn’t see where he was. Because of that notorious English cloudy weather, you know.

The concept sounds a little like 1941’s Here Comes Mr. Jordan (which I like better, because Claude Rains is in it). It goes in a different way, though. It goes from the Niven character wondering if it’s all in his head, to others being sure it is, to a concluding (and completely batty) “trial” scene in Heaven, which appears to be more than anything an airing of grudges between Enlgand and America.

Writers/directors Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger were approached by the British government about doing a movie to decrease tensions which had arisen from the presence of US troops in Britain. A popular phrase ran that the Americans were “overpaid, over-sexed and over here,” reflecting how some young British ladies enjoyed dating the Americans who had more money to spend. (And were also interestingly foreign, and most of whom were in great physical shape — which I’m sure helped their appeal!)

Per the Criterion booklet essay by Stephanie Zacharek, Pressburger told the government official “we have already said all this for you with 49th Parallel, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing, Colonel Blimp, and A Canterbury Tale. Are you suggesting that we make a fifth film to prove to the Americans and the British how much they love each other?”

The government official said yes. So Powell said, “It’s a tall order … You wish us to write a story which will make the English and Americans love each other, with a mixed American and English cast, with one or two big names in it, and it obviously has to be a comedy, and spectacular, and imaginative, and you want it to be a success on both sides of the Atlantic, and you want it to go on playing to audiences for the next fifty years.”

“Thirty years will do,” the official replied.

Zacharek includes the story to show how marvelously inventive Powell/Pressburger were, but I think the story shows how tired the idea was.

Personally, I can’t think of a single WWII “boost morale” movie that’s any good, at all. Two of the most disappointing Preston Sturges films have “rah rah the troops” sentiments in them. (And Eddie Bracken.) Maybe something like To Have and Have Not with its silly plot involving French resistance characters; the movie doesn’t take the plot seriously, which is why it’s still fun.

So Powell/Pressburger try to jazz this morale movie up a little. About a third of the plot is about whether or not Niven is imagining the whole thing in his mind, as a result of various head traumas. P/P did some research on epilepsy, which can produce hallucinatory “visions” in some cases; the word “epilepsy” wasn’t used, however, because there was considerable stigma about it at the time, grr. (Grr at the stigma, not at P/P for avoiding the word, that’s a very understandable choice.)

Another third takes place in heaven, although it’s not referred to as such by name. And it’s shot (by expert cinematographer Jack Cardiff) in an unsusual way; Earth is in color, “heaven” in black-and-white. It’s a curiously stark, drab, almost ghostly sort of heaven, where most of the heavenly officials seem as serious as Vulcan high preiestesses. We’re shown a view of a giant room, seen from a great height, where thousands of faraway specks (provided via special effects/animation) are said to be clerks recording the details of every life lived on Earth. Presumably to decide who’s allowed entry? It’s a curious theological concept, to be sure!

The drabness of heaven lends (some) logic to Niven’s not wanting to go there. He’s approached by his “conductor,” and told it’s his time to join the afterlife; he’d rather not, thank you very much — he’s just fallen in love. Although he’s told his beloved will eventually be in heaven herself, it’s not much of a comfort to him. I do wonder how that heavenly “reunited with friends and loved ones” works out for people who’ve gotten remarried after a spouse died. Does that become like an afterlife timeshare? I suppose I’ll find out, or… not.

That “conductor” is played by Marius Goring, an English actor. He plays the character as very stereotypically French… and so incredibly effeminate, Oscar Wilde would have booted him outta the cast of Importance of Being Earnest. It’s… it’s a LOT, as they say.

The heaven stuff ends with a “trial” sequence, where the “prosecutor” is an afterlife American (a rather annoying Raymond Massey) thundering about Freedom, and the “defense” represented by a kindly Brit (Roger Lively). It’s basically about which country is better than the other, and it’s really bonkers. At one point, the defense objects to this “jury” being composed of various afterlife humans whose countries were wronged by British imperialism (China, India, Ireland, etc.). So the prosecutor agrees, and the jury’s replaced by people from China, India, Ireland, etc…. who are all American citizens. The Great American Melting Pot! And, like all such odes to America’s amazing technicolor dreamcoat, now completely archaic. A realistic “trial” now would be between Boris Johnson and Grover Norquist arguing over which country has been better at purging the furreners and ending old age/disability pensions.

I do like Lively in this, immensely. He’s a large guy, with a great, soft voice. I liked him in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, too, which has a plot almost as wackadoodle as this one (Deborah Karr plays one woman two men pine for, then two sisters who marry the men, then a third, unrelated lady who becomes a love object when one of the sisters dies… it’s that batty.) And I LOVED Lively in I Know Where I’m Going, by far my favorite Powell/Pressburger movie that I’ve seen of theirs, yet. David Mamet said Lively was his favorite actor, but don’t hold that against Lively, he’s a sweetheart in Going. Mamet also loved Galaxy Quest. You wouldn’t hold that against Galaxy Quest, now, would you?

David Niven… to me, that guy was always one helluva drip. He was good friends with William Buckley, and that tracks. Not because of the politics (Barbara Stanwick was very right-wing, and I think she’s pretty good), but because Buckley was a helluva drip. Just watch any old clips of the guy. He wants to be Lord Snoffington-on-Trombleshire so bad, I’m surprised he didn’t go to English dentists for the proper tooth adjustments. I think I liked Niven in The Guns of Navarone. When I was around eight years old. He’s OK in the very first scene, here, when his plane’s going down, and he’s quoting classic poetry from memory to the nice voice on the radio. After that, he’s a drip.

Speaking of classic poetry… there’s a moment in the heavenly “trial” when the American prosecutor grants how the British have the best, greatest literature. Now, just hang on a minute, there. Yeah, they have Shakespeare and Ben Johnson and Chaucer, but America didn’t exist yet. When it comes to poetry, wouldn’t most literary scholars consider Whitman one of the greats? Henry James died a British citizen, but he was born an American one. And there are cultures far older than America/England which would consider our pretensions to literary greatness the refrigerator crayon drawings of toddlers.

Along with Lively, I did like Kim Hunter as the American radio operator/love interest. She was pretty new to screen acting at this point, and a little unpolished, but not in a bad way. She’d have been better paired with Lively as they paired Niven off with Lord Snoffington-on-Trombleshire, and everyone would live happily ever after. Literally, ever after.

There’s quite a few clever visual effects in the movie. Those who love it (and there are some who really do) absolutely have to check out the Critereon DVD with modern effects experts explaining how all this was done. A showpiece effect was a giant stairway, that looks to be a sort of marble escalator. They did, in fact, build this thing, and it did work. (And when actors step down it very very quickly, I want to scream, “no handrail, oh no!”) In America, the movie was titled Stairway to Heaven, and the sequel Misty Mountain Hop.1

There’s also an extra feature with longtime Scorsese editor Thelma Schoonmaker (who married Powell) explaining some of the difficulties in mixing B&W/color film. There was a color sequence in Raging Bull, and the only way to make it look right was to physically splice (that’s cutting and taping/gluing) color film into the B&W projection prints. Fun little trivia for fans of that movie, I’m not one of these.

Actually, my favorite effect in Life and Death isn’t an effect at all. When Niven’s character is undergoing brain surgery near the end, and he’s hovering between survival or not, the costumes and set design mix color/B&W very cleverly. It’s a cool visual idea and cost less than building a big escalator. (The big escalator could have been nearly dupicated with a big cheaper staircase and some good crane shots, by the way.)

Oh, and the opening effects scene is pretty cool, just the camera gliding through space as stars whiz by at different speeds. Schoonmaker says she doesn’t know how this was done. I do, I do! But I won’t spoil it, for those who like a sense of Mystery.

I made that last part up. But Stairway was the American title!