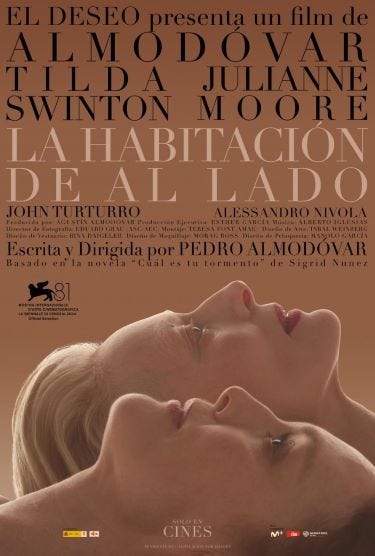

The Room Next Door (2024). Grade: B

I’ve always adored Tilda Swinton. Sure, she’s kinda otherworldly (John Oliver had some fun with this). The otherworldliness is part of what’s great about her; she doesn’t seem to be doing what any other actor’s ever done. With anybody else in the part, We Need To Talk About Kevin would be a Lifetime Channel movie; with Swinton, it’s interesting. She’s never not fascinating to watch.

(And no, I haven’t seen her in a Marvel movie, and no, you can’t make me.)

In this, Swinton’s character reconnects with an old acquaintance (Julianne Moore) whom she hasn’t spoken to in several years. Swinton’s character is dying of cancer. She doesn’t have any immediate family; she’s estranged from her daughter. So she makes a big, odd request; will Moore be there when she ends her own life? She doesn’t need help to do this; she’s got the medication for it. She just wants to know that someone else is in the same house when she does it. In the room next door.

It immediately makes you ask yourself: could you do that for someone? I don’t know. Especially if it was someone I didn’t know very well. I have no moral issue with a dying person choosing the timing of their own death; I consider it a mercy in many cases. The great novelist Terry Pratchett wished to have this option when he was dying of Alzheimer’s; he could not, as it is banned in England. There’s a BBC documentary about this, Terry Pratchett: Choosing to Die, available on YouTube. There’s another, stunning and beautiful documentary called How to Die in Oregon, where obtaining this medication became legal in 1997; a ballot measure to repeal it was voted down, 60% to 40%. Polls show it is generally supported by a majority of Americans, although as yet it is only legal in eleven states (plus D.C.)

The Room Next Door's director, Pedro Almodóvar, is a legend in the independent/arthouse film world. He’s made movies since 1980; this is his 23rd feature. I haven’t seen all of them, but I’ve enjoyed the ones I have. He’s got a wry wit to his movie making; the films are often doing social commentary without feeling preachy. They’re just what Almodóvar thinks, you don’t have to think the same way. And the same’s going on here; this isn’t an issue movie, it’s not trying to convert you (How to Die in Oregon definitely does.) It’s just what Almodóvar thinks.

It’s his first film in English (all the previous ones were in Spanish), and Almodóvar wrote the script in English, by himself. (It’s from a novel by American writer Sigrid Nunez that I haven’t read.) At first, it almost feels like Almodóvar’s command of English is too wobbly. The words and grammar are correct, they just feel stilted and forced. (Of course, talking with an old acquaintance you’ve just found out is dying might very well feel stilted and forced.) There’s a flashback which is like something out of David Lynch parodying rural Americana; a house in a perfect field and nothing on the horizon. It’s on fire, and a man thinks he hears voices inside, and runs in to his death. You wonder when the movie will start feeling real.

It does, after half an hour or so. Especially as the plot gets going. Swinton has rented a house in the country for a month for the two of them to stay at. Every night, she will leave her bedroom door slightly open. If Moore ever gets up and sees that it’s closed, that will mean Swinton took the medication. This has its own tension and fascination to it, and there’s some obstacles along the way.

Something I really appreciated about what Almodóvar is doing here is how he can show these comfortably upper-middle class people and not make you want to yak at their relative affluence. (Moore’s friend and ex, John Tuturro, is also a writer, giving college lectures in upstate New York.) Maybe it’s because you don’t get the sense Almodóvar is a snob about social class. He doesn’t think these people are better than poor people, they’re just not poor. When Cate Blanchett in Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine falls from affluence to living with the poors, it’s shown as the worst thing that could happen to anyone. Not the poverty part; the knowing poor people part. The poors are all tasteless and awful. Maybe that’s why I’ve always felt uncomfortable with the characters in Woody Allen movies; they’re people who would be disgusted by the likes of me.

Moore’s quite likably bright here. She’s often played dimwits, like in May December and Cookie’s Fortune; she may relish that challenge, but I don’t care for those roles. (I was torn on her character in The Kids Are Alright, almost an Allen movie set in L.A.; that character wasn’t a moron, but she sure wasn’t nice to the landscaping crew.) Here, she merely seems a decent person doing her best with a tough situation. Tuturro’s likably grumpy about the students he meets — those darn kids today! — and a useful ex to have; he knows where to find Moore a lawyer, which proves to be a very good idea.

And Swinton is simply stunning, as usual. A couple of times she turns to silently face the camera, and it’s like watching the eyes staring at you in the end of 2001. Her character is frightened, angry, making a huge imposition, and she’s extremely apologetic about all these things. She’s also very emaciated; did she lose weight to play this, or is she naturally very thin? I wasn’t able to find out, although I did find out that Almodóvar was once offered the chance to direct Sister Act, which is a hoot to imagine.

Incidentally, if you’re like me, you might spend part of this movie wondering how old Moore and Swinton are, respectively. Almost the same! November 1960 and December 1960. Also born in 1960 is frequent Almodóvar collaborator Antonio Banderas. Small world.

This is a good, effective movie about a depressing subject that’s not depressing to watch. Considering that one of the main characters is dying, it ends in a satisfying way. You don’t have to watch them die, like in How to Die in Oregon or the fiction movie Paddleton (where those scenes are touching, yet hard to watch).

I need to see more of Almodóvar’s films, and rewatch the ones I saw so long ago. I just like the guy. I’m glad he worked with Tilda Swinton, and I hope they do again. They’d actually done a short film together, The Human Voice, which would have made a nice addition to this DVD. Why didn’t you buy the rights and put it on here, Sony Pictures Classics? Typical dumb studio thinking.