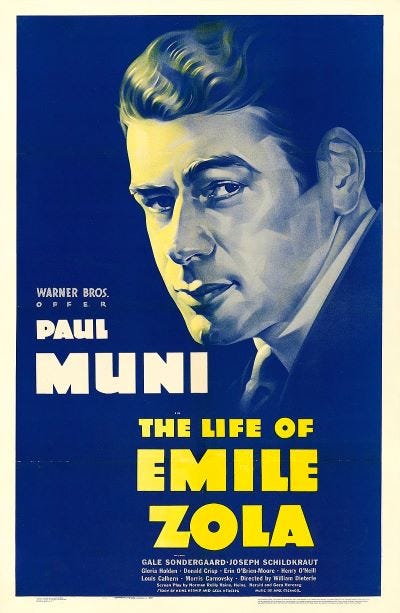

The Life of Emile Zola (1937). Grade: B-

I’d never seen anything with Paul Muni in it, despite him being one of the most popular/acclaimed actors of his day. He was frequently in prestige Hollywood roles, and was cited as an inspiration by Brando & Pacino, among others.

How is he in this? I think he's perfectly alright. Some critics, like the half-bright Andrew Sarris, thought he was a terrible overactor. So, at times, did his director in this film. (Couldn’t you tell him to try it differently for another take, then, if you were so superior about it?)

I happen to think Muni’s fine, and quite warm/winning in his quieter scenes. In the bigger ones, he plays to the back of the audience rows, a bit — but that wasn’t uncommon for actors with stage experience. And especially ones with considerable stage/silent film experience. They came from mediums where you had to be broad to get emotions across.

What’s more, some of the dialogue here practically demands melodramatic acting. Here’s a bit quoted by IMDb:

La Rue: Then go ahead with your scribbling. And maybe a lean stomach will teach you better!

Émile Zola: But a fat stomach sticks out too far, Monsieur La Rue. It prevents you from looking down and seeing what's going on around you. While you continue to grow fatter and richer publishing your nauseating confectionary, I shall become a mole, digging here, rooting there, stirring up the whole rotten mess where life is hard, raw and ugly. You will not like the smell of my books, Monsieur La Rue. Neither will the public prosecutor. But when the stench is strong enough, maybe something will be done about it.

That’s the sort of Hollywood Message that almost always falls flat, and is still done today.

Aside from the corny dialogue (at times), this script is actually decent. The movie zips along at a nice, very watchable pace — it rarely feels slow in its two hours.

The title’s a bit misleading. It isn’t, really, about Émile Zola. It kind of sort of is, for the first 45 minutes or so. Zola starts off poor and cold, becomes a famous, rich author… and comfortably secure in his position. Where the story really takes off is when he’s asked to help out in the “Dreyfus affair” (as it came to be known). Where Zola has to step up from his comfortable wealth.

The Dreyfus case isn’t one I know much about, although it was world-famous at the time. The movie was made 40 years later, so most viewers probably had some idea of the situation. Here’s an 1898 French cartoon, from Wiki, depicting how divisions over the case could ruin family gatherings:

So, politics were disrupting Thanksgiving dinner back then, too… (ok, the French don’t have Thanksgiving, but you know what I mean).

All I knew about the case was it was a famous example of antisemitism run amok. I’ve now read a few quick summaries of it, and would need to read a book on the subject to grasp it, but I think antisemitism run amok is a good enough understanding to start with.

Alfred Dreyfus was a French military officer, from a part of France with a heavy German cultural influence (it’s right on the border and has switched ownership in several conflicts). When certain French military secrets were leaked to the Germans, panicky military officials were looking for someone to blame, and blamed Dreyfus, without any real evidence. Almost certainly because he was Jewish, and antisemitism was widespread in Europe at the time.

Having virtually no evidence, the military officials forged some. One intelligence officer, Georges Picquart, basically found out who had leaked the information. And was told to shut up about it, as it would make the military look bad for prosecuting the wrong guy. He did his best to make the truth known anyways, and got in a lot of trouble over it. The real leaker was given a show trial and quickly acquitted, then booted from the military. He went to England soon after. Dreyfus was sent to a horrible penal colony on French Guiana.

The movie has Dreyfus’s wife approach Zola for help. This doesn’t seem to have actually happened. But Zola did take a passionate interest in the case, along with many other artists/intellectuals of the time, and was probably the most famous name among them. He wrote a long letter on the front page of a newsletter accusing French military officials of lying and covering up lies; it was hugely popular and widely-read.

And this resulted in Zola being tried for libel. Which, at least per the film version, was his intent; to make the broader public aware of the story. The presiding officer of the court, under political pressure, didn’t allow Zola’s defense to re-examine the Dreyfus case, although the public learned the truth they hadn’t known before (as the press was filled with far-right publications that loved to spread antisemitic falsehoods).

Eventually, as you’d expect in movies, justice does prevail after many setbacks/obstacles. And the script/direction gives Joseph Schildkraut, playing Dreyfus, a wonderful moment of hesitancy/fear/realization when he’s finally freed — although I wanted a tearful reunion scene with his wife, and for some reason there isn’t one!

Zola’s passion for truth is reignited, and truth wins! And while he dies in the end, his memory will live on as the fight for truth and against intolerance grows ever nobler.

Only one thing, though — the movie doesn’t say that Dreyfus is Jewish! The word wasn’t in the script! And this was made in 1937. Clueless Americans might not have known what was going on in Germany in 1937, but most American Jews did. Muni was Jewish. So was producer Hal Wallis — who, along with producer Henry Blanke, oversaw the creation of the script.

Some historians have accused Hollywood of active collaboration with the Nazis, but the truth is probably more homegrown than that. David Denby’s 2013 article “Hitler in Hollywood” points out that studios weren’t making much, if any money from releasing films in Germany (aside from a few newsreels). Warner Bros. (the Emile Zola studio) had pulled its films from Germany since 1934, after one of their Jewish employees was attacked by Nazis.

What the studios were likely afraid of was offending American antisemites.

The Hays Code, Hollywood’s guide to self-censorship, had been established in 1922, after some celebrity scandals had moralists in high dudgeon over the “indeceny” in movies. Yet it wasn’t really enforced very much until 1934, when hardcore Catholic Joseph Breen was put in charge of the Code.

Film historian Thomas Doherty wrote that Breen was extremely antisemitic before coming to Hollywood; less so afterwards, and eventually voiced support for groups decrying bigotry. And there was a lot of it going around. Here’s a 1938 leaflet circulated in Hollywood and the Midwest:

Hardcore Catholics who wanted more Hollywood censorship frequently tolerated this sort of sludge, whether or not they were personally antisemitic, themselves. Funny how religious extremists will cozy up to bigots when they share the same moralistic goals.

Doherty wondres if Breen really did have a change of heart, or if he “was smart enough to keep his true feelings to himself and suck up to the men who were buttering his bread.” (Doherty suspects it was a real change of heart, I’d guess maybe a little column A, a little column B.)

In any case, before his change of heart, Breen had agreed with those who didn’t want anything made which painted Germany, or Nazis, in a bad light. If movies made antisemitism look bad, that made the antisemites criticizing Hollywood morals look bad. You can’t have that. Breen made sure to kill a 1933 script called The Mad Dog of Europe that portrayed how Hitler attacked Jews; it was written by Herman Manckiewicz. He’d later go on to write Citizen Kane.

David Denby’s article also mentions the fear of stoking antisemitism among studio heads. (It was Jack Warner who personally called for the removal of any mention of Jews in the Emile Zola script.) All the major studio heads (except Daryl Zanuck at Fox) were Jewish; all of them worried that if there was enough backlash to Hollywood, they could lose their studios.

There was an influential movement called “America First” at the time which was against any opposition to Germany. Some of the America Firsters were principled opponents of World War I, which they saw as being a senseless waste of human life we should never have gotten involved in. (I happen to agree with this, and so did many Americans, and Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was frequently involved in punishing those anti-war Americans, before he got named Commissioner of Baseball.)

Other America Firsters were staunch antisemites like Henry Ford. They believed that Nazi persecution of Jews was either a good thing, or grossly exaggerated. (Charles Lindbergh seemed to believe it was real, and terrible, and therefore American Jews should… not want war with Germany? That’s more than a little bit confused, Chuck.)

So movie studio heads felt themselves to be in a tough position. They may have personally loathed Hitler. But they were afraid that if they made movies criticizing Hitler, or Germany, or antisemitism, it could spark a backlash among those who thought any talk of antisemitism was propaganda to get us into war. Denby writes:

“Breen tormented them with the spectre of what anti-Semites might do as a way of stifling their response to what anti-Semitism was already doing—and would do, in Europe, with annihilating violence. It’s as if the Hollywood Jews had become responsible for anti-Semitism. Of all the filmmakers in the world, they became the last who could criticize the Nazis. Their situation was both tragic and absurd.”

(And meanwhile, the Hays code under Breen was censoring many many other things in movies too, without specifically tying them to hardcore Catholic morals, lest that stoke anti-Catholic sentiment… so, as one critic wrote, we ended up with “a Jewish-owned business selling Catholic theology to Protestant America.” The Catholic Legion of Decency remained influential in censorship until the late 1950s.)

One last note on the politics of Emile Zola; the director, William Dieterle, was a German-American who fled Germany in 1930 to escape the worsening political situation. And he made an anti-Franco, anti-Spanish-fascism movie, Blockade, in 1938. (That got him disliked by the McCarthy people years later.) And he made a 1942 biopic of mega-racist, idiotic and incompetent President Andrew Johnson, showing how Johnson pulled America together, rah-rah. When progressive groups complained about the film’s portrayal of Johnson, Dieterle defended the film… in the pro-socialist Daily Worker. Sounds like an odd duck, this dude.

In any case, most film buffs should probably check out at least one movie starring Paul Muni, just to get a sense of who he was and why his films were popular. And this is an entertaining one! If you’re not going to learn a lot about the Dreyfus affair from it, you’ll still at least pick up the gist. There’s a small but very effective role by Charles Richman as the presiding ruler/judge at Zola’s libel trial; when Richman rules again and again for the prosecution against the defense, you’ll be as furious at him as Zola is.

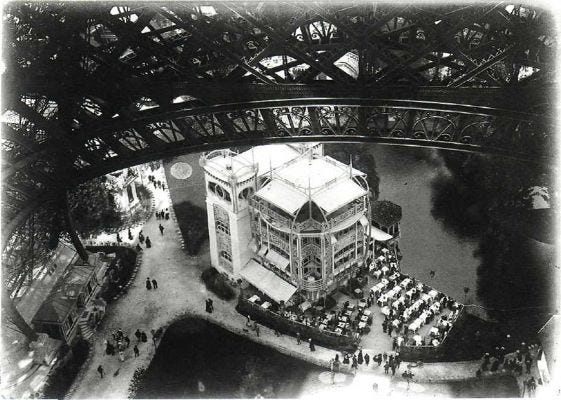

And Zola himself seems like he was an interesting fellow. In his late 40’s, he got the photography bug from a newspaper editor, and Marcelo Guimaraes Lima shares a few of Zola’s photos on this website. Here's an excellent one:

I’ve known people who spent years perfecting the technical craft of photography, but who never had “the eye”: that instinctive feeling for when an image will just look striking on film. At least in that photo, Zola did! And he also fought for truth and justice, too, let’s not forget about that. We’ll just add photography to the list.