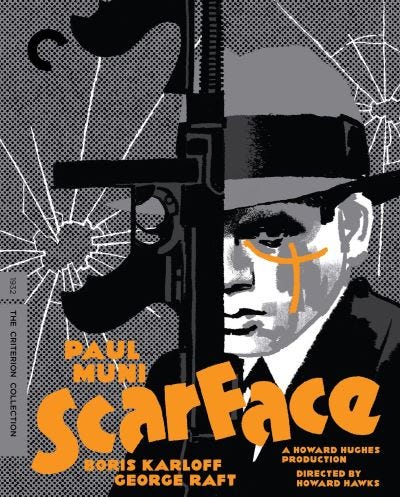

Scarface (1932). Grade: B-

The first title on the screen reads: “This picture is an indictment of gang rule in America and of the callous indifference of the government to this constantly increasing menace to our safety and our liberty. Every incident in this picture is the reproduction of an actual occurrence, and the purpose of this picture is to demand of the government: 'What are you going to do about it?' The government is your government. What are YOU going to do about it?”

Or, as screenwriter Ben Hecht promised producer Howard Hughes: “double the casualty list of any picture to date, and we’ll have twice as good a picture.” (That’s from the Criterion essay by Imogen Sara Smith.)

It was 1932, the Depression was on, and one way to guarantee that your movie made money — or at least got a lot of publicity — was to have it full of Daring Elements; sex, violence, and celebrity stories were always noticed. (Unlike today.) Everyone knew who Al Capone was; everyone knew his nickname was Scarface.

This is based on a book by “Maurice Coons,” the pen name of the even weirder name Armitage Trail. It was published in June of 1930, and Trail was invited to Hollywood to work on scripts; he’d die in October of 1930 at a Los Angeles movie theater, at the age of 28. He’d lived in a Chicago suburb for a while, and knew a lawyer who knew some gangster-ish sorts. His book wasn’t a biography of Capone, just a mostly-invented story about a very similar type of ambitious thug.

Inheritor of oil-drilling money Howard Hughes was busy trying to bang every famous woman in Hollywood at the time, and had financed several popular movies; The Racket was about Chicago gangsters, and The Front Page about newspaper reporters on the Chicago crime beat. Hughes hired one of The Front Page’s writers, Ben Hecht, to adapt the book; wisely, Hecht didn’t trust Hughes one whit and demanded to be paid daily.

Paul Muni (born Frederich Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund) had been a enormously popular Yiddish stage actor; Scarface was his first major role. It’s a hammy turn, but mostly in a pretty fun way. Muni’s Scarface is almost always performing for others, anyways. He’s putting on a show, playing the friendly crime pal, the high-living, carefree young success, the tough guy you better respect or else.

He’s only Emoting in the scenes with his sister, played by the freakishly thin Ann Dvorak. He doesn’t want her dating; she wants to go out and party with the boys. Hecht wrote this, per Pauline Kael, as “the Borgias set down in Chicago.” It’s pretty clear that Scarface basically has the hots for her, and she loves the fancy clothes he pays for. At one point, she does a slinky-seductive dance in front of Scarface’s gangster pal George Raft; this was a recreation of the dance moves Dvorak had actually done for Raft at a party. She’s possibly the most likable character in the movie, although her acting skills were pretty raw at the time. You sympathize with how much fun she sees her brother having, and how pent-up she feels because of his controlling weirdness.

The director, Howard Hawks, had made an Aiplane Fighter Aces movie at the same time Hughes was making one of his own; Hawks pilfered half of Hughes’s stuntmen, made his movie on a much tighter budget, and it was a much bigger success. Hughes told Hawks and Hecht to amp up the violence in this one, and they were happy to agree. It was 1932; the Hays production Code wouldn’t start being really enforced for a few more years.

On Wiki’s page about the Hays Code, they have this fabulous picture made by pin-up photographer Whitely Schafer:

That’s listing some of the many things the Code banned. And Scarface has most of ‘em.

The movie’s most fun when it’s piling on the mayhem. When you’ve got a montage of machine guns blazing as pages get ripped off a wall calendar; as bullets are thrashing the heck out of one set after another. There’s a scene where one guy keeps yelling “I can’t hear you” into a pay phone as bullets nearly tear his head off 100 times; it makes no sense why he isn’t ducking, but it’s a hoot anyways. There’s another scene where a gangster wants to shoot out of a window that’s already been smashed; still he throws a vase through it anyways just to SMASH MORE.

Although the Code wasn’t fully in effect, the cesnors took note of all the Wrongness anyways, and forced the filmmakers to include both that preachy title card plus a preachy judge at the end. Scarface dies in the original version; the revised version has him caught, tried an convicted. The censors, probably correctly, thought the original basically has Scarface going out the way he always wanted to.

You know who really went out the way he always wanted to? George Raft, who plays Scarface’s mostly loyal, coin-flipping henchmen here. Raft was a fishmonger before he dropped out of school at age 12! He was a professional boxer in his teens, then a independent-league baseball player, then a dancer — a paid one! A “taxi-dance hall” pro, which meant customers paid for the dances, which were definitely sultry in nature. (It’s what the musical Sweet Charity is about.) Raft said “I could have been the first X-rated dancer … I was very erotic. I used to caress myself as I danced. I never felt I was a great dancer. I was more of a stylist, unique. I was never a Fred Astaire or a Gene Kelly, but I was sensuous."

Raft got into movies while he was dancing in Los Angeles, and Scarface made him a huge star. He had affairs with Betty Grable, Marlene Dietrich, Tallulah Bankhead, Carole Lombard and Mae West, among others! When his movie career stalled out, he took a job as a front man for a mob-run Cuban casino; after Castro kicked the mob out, Raft eventually was offered a role as a gangster in Some Like It Hot (where he gets a joke about a coin-tossing guy). Raft worked for the mob, parodied the mob, testified against the mob, and somehow never got murdered for it! Maybe the gangsters liked his movie characters too much to bump him off.

Several moralizing critics at the time took umbrage with all the violence in this; there’s always gonna be some spoilsports. (There’s not even any blood in the movie, just a whole lot of extras maxing out “slow falling death” from gutshot wounds.) Apparently, Howard Hughes had his feelings hurt that the movie offended some people, after Howard Hughes had specifically told Hawks/Hecht to squeeze in all the mayhem thay could! Well, he was a crazy person. Hughes never let the movie be re-released again; it only became available after he died in 1976.

Brian De Palma did a bloodier version in 1983 from a pretty terrible Oliver Stone script (starring Al Pacino, an admirer of Paul Muni). What that version gets wrong is taking this material seriously and making it last almost three hours. This is sheer shoot-em-up silliness and doesn’t need more than the 95 minutes it got in 1932. Come for the bullets and broads, stay for… well, bullets and broads. (Karen Morley is also thin and gorgeous and fun.) That’s the good stuff, at any rate. There’s a Boris Karloff sighting, too! He’s an Irish gangster who talks like a British guy, because Karloff was a British guy.

And, for anyone watching the Criterion DVD, be sure to put on the feature where crime fiction author Megan Abbott and writer/actor Bill Hader absolutely geek out over Scarface for half an hour. I didn’t LOVE the movie the way they did, but they’re awfully fun to listen to, anyways. People who enjoy something, sharing their enjoyment, usually are pretty fun.