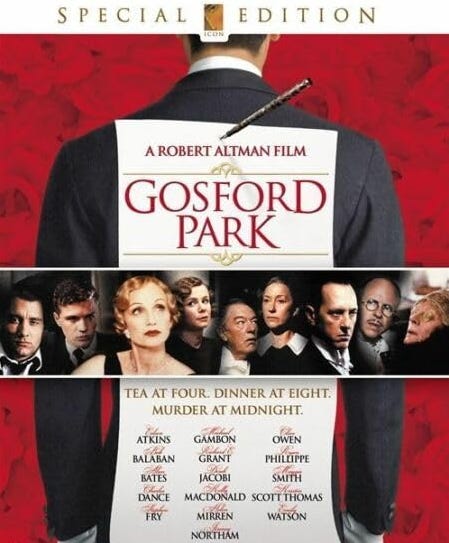

Gosford Park

One of Altman's best; a murder mystery (sort of) mixed with observations about class snobbery.

Gosford Park (2001). Grade: A

Thirty years ago, in college, I worked Thanksgiving dinner at a country club. (They’d put up flyers on campus for anyone staying in the dorms over Thanksgiving break; I think the pay was $75 or so for a few hours’ work.) Basically, my job was to serve/clear beverages. I was told that it was vitally important to “serve with the left, clear with the right” (meaning, which hand to use). I should stand next to the table when I wasn’t fetching drinks, and refill glasses/clear away empties without speaking or being spoken to.

I managed this reasonably well — I did drop an entire tray of wine glasses in the kitchen, but nobody cared. Staying ever-present and ever-silent; that was the main thing. What was odd about this is how the dinner guests behaved around the wait staff; they both did know you were there (a wave of the hand meant “no refill needed”), and acted like you weren’t. There was a huge heated discussion about who was getting what in the rich old patriarch’s will. People saying very nasty things to each other! And not remotely caring that I was listening.

“The maid will be in the room, and they pay no notice. It could be a dog,” said director Robert Altman. And it’s behavior I’ve seen elsewhere. Like the time two corporate higher-ups at my company needed a private room at the main office in which to have an impassioned breakup. Since one of them was married to somebody else. They found a private room, or at least one without anyone real inside. Only me, doing a ton of paperwork. Right there. They had to walk by me to get in, and sat in chairs on the other side of my cubicle. And went at it: tears and threats were exchanged. Again: I was RIGHT THERE.

There’s a scene early on in Gosford Park where a couple are having a secretive moment, and the lady notices a servant nearby (Richard E. Grant); the man says don’t mind him, he’s nobody. And that’s how these sorts think of servants, of waiters, lower-down employees; nobodies. “No” as in not equally human; “bodies” when you want them to do things for you or have sex with you.

It’s to Altman and the cast’s tremendous credit that they show a huge range of variety in these relationships. There’s snobbery among the servants as well as among the upper class. The servants all eat together, and are assigned table seats based on the social standing of who they serve; an upper class person who can’t afford as many servants is considered inferior to her peers. Most of the servants enjoy sharing juicy gossip and issuing nasty putdowns of their half-bright richies; but the head butler and head housekeeper will hear none of it.

There’s a moment late in the film where one of the rich guests (Tom Hollander) is feeling a bit bummed; he’d hoped to get the family patriarch to help him out financially, and it’s not gonna happen. He opens up, of sorts, to the kindly maid in the room: “Why is it, would you say, that some people seem to get whatever they want in life? Everything they touch turns to gold. Whereas others can strive and strive and have nothing. I wonder, do you believe in luck? Do you think some men are lucky and some men just aren’t and nothing they can do about it?”

He IS lucky — the kindly maid (Sophie Thompson) is nursing a huge, unrequited crush on the head butler. So she tells Hollander that love’s the most important thing in the world, and he seems cheered up a little by her words. But imagine if you were in her situation, and you weren’t thinking about your romantic dreams at the moment?

A guy who has it a zillion times better than you ever will, just because of the family he was born into. Someone like that complaining about their rotten luck! The scene is played kindly — she’s not as sarcastic as some of the other servants, and he’s not as nasty as some of the others served. It’s close to a human connection. Yet it’s a connection between unequals, just the same. If she’d run across him in a quiet room and started talking about her heartbreak, he could fire her on the spot.

I’d be more like a different servant in another scene, after she’s made a mistake that resulted in her firing. Her rich lady asks, not really caring much, if the servant will be alright. She says I’m only unemployed with nowhere to live, so I’m just FINE. (Actually, I’d probably just say “yes, ma’am,” because I hate confrontation — but I’d be thinking snarky thoughts!)

The entire cast is extraordinary, which is vitally important here. Keep in mind the number of characters we have! There’s well over 20 people we have to follow — and the servants are sometimes referred to by their own names, sometimes by the name of the person they’re assisgned to serve! Yet you’re almost never confused as to who you’re seeing (maybe with a few of the younger rich folks, although that doesn’t matter in the grand scheme of things).

The credited screenwriter is Julian Fellowes, who’d go on to write the hugely popular Downton Abbey TV series; it has some of the same master/servant dynamic, without anywhere near the critical bite. One interesting thing about when this was made is that there’d been a huge number of recently successful British movies/shows based on novels about the upper class. (The Merchant Ivory movies A Room With a View and Howard’s End, multiple Jane Austen adaptations, books by the Bronte sisters, etc.)

All of these had a hint of social criticism about them — for example, the fate of upper-class young women being totally tied to who they marry — yet they could also serve as luxury fantasy for wanna-be snobs. Downton Abbey was very much in that mold, and even had a maudlin Gone With the Wind vibe, lamenting that this ridicuolus way of life would soon be lost forever! Rich people still have servants today, but the servants have many other job options, they’re not afraid their lives will be ruined if they’re fired. (Of course the rich people who rule us now are very much trying to make us all afraid, again.)

It may be Fellowes’s script here, but every Robert Altman movie just uses the script as a starting point, and encourages the actors to improvise in character. Altman and cinematographer Andrew Dunn used a couple of constantly-slowly-moving cameras, which doesn’t call attention to the camera style at all; it’s so your eye can wander from one piece of the frame to another. To see one character or another, one object in the room or another. (Rather wittily, for a murder mystery, there’s multiple shots of items that can be used in a murder — and multiple items ARE used eventually!)

Ah — that murder mystery. It’s not really much of a mystery — you’re not given many clues in the classic Agatha Christie style. And the way it happens is probably the movie’s biggest script flaw. As it turns out, there’s two murderers, one of whom commits a murder to protect the other. Which would require ESP. And I don’t really buy the motive of the murderer being protected, either. There’s also a late reconciliation between two characters who’ve been on edge with each other for many years; it’s very affecting, since the actors are masters, yet I think it’s sprung on us too quickly.

Actually, for me, the climax of the movie comes about two-thirds of the way through, when it simply pauses for a long, gentle stretch. Jeremy Northam (so good in Dean Spanley) is a succesful movie actor who’s been invited to the rich folks’ home because they regard movies as a curiosity; he’s there to be the dancing bear, to alleviate their boredom. (It’s wonderful how dull this movie shows a life of luxury as being, and how dull most of the people are who live it — a nice change from “the rich are mean but fascinating!” vibe in movies like Titanic.) Northam isn’t a member of the highborn class, he just knows how to convincingly play one.

He starts singing some appropriately period-sounding songs, and soon finds out that he’s got a devoted listener (the wonderful Claudie Blakely). Blakely’s been looked down on by the other guests for being less rich; her husband hates her for it, and is cheating on her, and constantly tells her how ugly she is. (Of course Blakely is perfectly attractive, just not in the upturned button-nosed style the others consider pretty.)

As Northam sings his gentle, amusing, romantic songs, she’s emotionally transported. To a world of love, and happiness, and joy, a fantasy wonderland she knows she’ll never have. And Northam, who knows that the others look down on them both, is singing basically just for her. Not to woo her, he hangs out with Hollywood starlets all the time! But to give her that fantasy, just for a few minutes, to let her dream happy dreams. And the servants hear the kindness in his voice, and quietly hide in adjoining rooms to stop and listen. (While the richies mostly ignore him — but he's no longer singing for them.)

It’s one of the greatest moments Altman’s ever achieved on film, where all of his quirks and methods and themes come together almost perfectly. The big cast, the multi-layered dialogue, the battle between money and feeling, it’s all there. And there’s some plot skulking around in the background, and you’re aware of it, and it doesn’t matter at all.

Incidentally, that big cast didn’t make getting investors to back this very easy! They were confused by the plot, so they assumed audiences would be, too. And they were worried about Altman’s age (he was 76), so they insisted that there was a backup director on standby — the very great British director Stephen Frears.

Those little, sweet fragile songs Northam sings? They’re all written by a very real movie actor/songwriter/playwright, Ivor Novello. Kind of a somewhat-lesser Noel Coward type. It’s the only character in the movie based on a real person, who really had been in a movie that Maggie Smith’s snarky character describes as a “flop.” (The 1932 sound remake of 1927’s silent The Lodger, directed by Alfred Hitchcock; the original was a big hit, and the remake wasn’t.)

There’s so many good actors in this movie, and so many wonderful, subtle moments, that I won’t really single too many out. But I loved Bob Balaban’s guilelessly cheerful American movie producer; when he makes a rather embarassing social mistake, he’s not embarassed at all, he just plans to use it in his next movie. (And when he gives one of the mistreated servants a ride at the end, you half-imagine the ride’s going to end with him getting her a job in the movies.) I remember being originally disappointed that Stephen Fry’s detective character was kind of a dolt, but now I think it serves the story terrifically; the way he arrogantly bumbles about while his underling is actually trying to solve the case.

It’s amazing how well these mostly British actors, from a theater tradition that’s very much about respecting the text, fit in so well with Altman’s improvisational style. It’s amazing how subtly good the score by Patrick Doyle is — he’s sometimes too overwrought when doing Kenneth Branagh movies. (But Branagh, who I do enjoy, is sometimes kind of overwrought himself.) The art/set direction’s by Anna Pinnock and the director’s son, Stephen Altman. It was sort of a joke around Hollywood at the time that those Merchant Ivory movies and those Austen adaptations always ended up winning Academy Awards, even though all the art/set directors really did was rent out an already-furnished house from an old artistocratic family that was short on cash! (Which you can imagine happening to the rich families in this movie a few decades down the road.) Yep, this one was done by renting houses from rich people, too — sort of an AirBnB for movie locations, these things. (One of these houses showed up in Branagh’s Peter’s Friends, as well.)

I’ll stop babbling; look at the amazing cast list and just see this. It has a special memory for me, since it was the last movie I ever saw with my mom; she absolutely adored English literature, and saw ALL the adaptations of classic British novels. And guess what other genre she loved? Murder mysteries of the Agatha Christie style. So it’s almost like this one was made for her. And for anyone I’ve known who’s seen it, too.