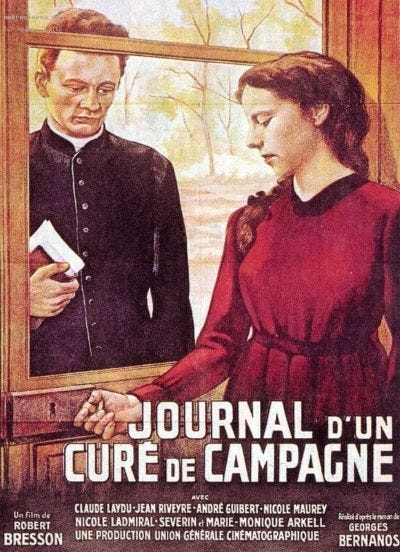

Diary of a Country Priest

Beautifully-made, highly frustrating, widely-loved French art film. Not my glass of wine.

Diary of a Country Priest (1951). Grade: C

Raise your hand if you’re perfect! Go on, I’m waiting. Now put your hand down, you big fibber.

Generally, we try our best to be decent people, when we’re able, and are a little disappointed in ourselves when we fail. Nobody’s perfect, or at least nobody I’m ever likely to meet.

The hero of Country Priest is young theater actor Claude Laydu, making his first film appearance. (He’d work more in film for about a decade, then became primarily known as a soothing children’s TV puppeteer.) Laydu wants his parish life to be perfect; he aims to be perfect; his own failings and the imperfections of his parishoners get in the way. He suffers a spiritual crisis, and the film asks us to share in his mental agony. (And his physical agony; the man’s not well. Laydu spent time losing weight for the part.)

But I had an awfully hard time relating to this character. I don’t know how he developed such an impossible vision of what his rural priesthood would be. He hopes that his ministry will be to the poor; he finds his time monopolized by the biggest local rich family.

Well, of course it is! Rural communities aren’t about the salt of the earth, they’re about which local bigshots wield power. In the olden days, they were feudal lords. Now, they’re local business owners or landowners who stand to make the most from selling town water rights to a oil company/giant Ag corporation.

I know people who have this fantasy view of rural life. It's silly, but I know them. I know why they have those fantasy views. This priest, I don’t understand. I don't think we're meant to.

In the Criterion essay by French critic Frédéric Bonnaud, we read that director Robert Bresson “wanted nothing less than a radical reform of the cinema’s perception of reality.” So that’s why Laydu’s character is so devoid of a background, I guess?

I like and respect stories about people wrestling with questions of faith. But I need to know why they believed what they believed to begin with. In Fred Zinneman’s excellent The Nun’s Story, you see that the Hepburn character was naive about what convent life and restrictions were, and you empathize with whay she wanted to become a nun in the first place — she wanted to bring healthcare to poor people. (The real woman who inspired that novel/film made a life of of doing exactly that — she was an impressive person!)

There’s moments where I feel like I’m starting to get Laydu’s character, here. When his stomach’s bugging him and all he can keep down is old bread softened by wine. Or when he feels like his superior is pooh-poohing his frustration at having to kowtow to the rich family. Yet nothing ever seems to teach this guy anything. And he’s not shown to be a stubborn dolt, so it’s hard to grasp why he’s only self-reflective in his diary pages.

And when he seems stunned that French people have affairs — for crying out loud, this is France! They’re sort of known for that!

The local rich guy is having an affair with his daughter’s governess; his wife is angry and resigned, his daughter angry and vengeful. The daughter takes out her fury on Leydu, upset that his magic clothes and empty words don’t stop her parents from being hypocrites.

Ah yes, the vengeful, sexually voracious teenage Bitch Demon. I’ve never been very interested in this sort of character — not in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, not in Heathers, not in the 1000 Mean Girls-type movies and TV shows and what-have-you. I laughed at how these characters made James Mason squirm in Lolita and Matthew Broderick in Election, but those are satirical comedies. Here, where we’re supposed to sympathize with the priest’s internal struggles, I wonder how he’s gotten through his teenage years without ever meeting any such characters before. Was he raised by saintly forest gnomes?

This film has been enormously praised by generations of critics, and enormously influential on other filmmakers. Scorsese cited it an an inspiration for his years of working to get Silence financed; Paul Schrader as an inspiration for his First Reformed. Well, I empathized with the characters in Silence; and First Reformed had Ethan Hawke being Soulful, which isn’t one of my favorite things.

I get why the movie impresses people. It’s impressively made. There’s hardly a shot that doesn’t involve choreographed camera movements, and vivid frame compositions, and a careful use of soft focus in some parts of the image. Critic John Gerlach mentioned that this soft focus creates a sort of halo around objects and characters at times; it represents the near-hallucinatory way that dazed, ailing Laydu sees the world.

Sure. And it also annoyed the crap out of me, and made me keep checking my glasses to see if they were smudged.

It’s intentional, though, and it’s definitely an effect. So we can congratulate director Bresson and cinematographer Léonce-Henri Burel for pulling it off. It’s not pleasant to watch. And it’s only meaningful if you think the “meaning” of a film is separate from its characters and story.

Critic Bonnaud seems to think so — and compares one precocious know-it-all kid in this movie to the creepy twins in The Shining: “knows too much about too many things, in a manner that’s all too visible.” Oh, boy, we’re in Shining territory. Where every moment of a film can be analyzed and analyzed and its meanings uncovered for those who Seek — what’s really in Room 237?

There’s one scene that deviates from this kind of Art Movie Artness, and it comes about halfway through. The rich guy’s wife, who knows her husband is cheating (and whose own past has been very French), has been consumed by grief for years about the childhood death of her son. You can almost imagine she’s pretty self-righteously miserable in it, although it’s hard to blame her for that. She comes close to telling the priest how this has made her question God’s existence, or God’s goodness; the priest comes close to admitting he’s felt the same way. It’s a kind of bonding.

Rachel Bérendt, who plays the rich guy’s wife, had been in a handful of movies since at least 1922, and was busy on stage. This was certainly her meatiest film moment, and she acts the hell outta the part. Laydu is just as good with her. For once, Bresson isn’t monkeying about with the image, or dissolving in/out of another annoyingly short scene; it’s basically well-filmed theater. (Exactly what critics worship this film for NOT being.)

And then we go right back to more blurry lighting effects and tortured voiceovers and such. I had hoped this scene marked a stylistic turn, and a move towards awareness for the character. I was Wrong. Bresson’s almost out to make you do penance for enjoying something that might work on stage. Because what you should appreciate is pure CINEMA!

I can appreciate it fine… liking it is another matter.

If you like watching rather miserable movies 10 times or more to find extra nuance in every shot, then you, too, might love this as much as the rather humorless Paul Schrader does. If you want a solid, well-acted story about wrestling with faith, watch The Nun’s Story — it’s 35 minutes longer this this, and less draggy, and more humane. And if you want to watch a French masterwork from the same period about human imperfection, watch La Ronde — it’s got camera and lighting effects every bit as impressive, and they’re meant to make you happy, not feel like you’ve got stomach cramps in your soul.

Pauline Kael wrote: “Does Bresson know what a pain this young man is? The priest's austere spirituality might give the community the same sort of pain that Bresson's later movies give some of us in the audience.” But she admitted that the film has, “in the end, a Bach-like intensity.” So I think I’ll leave it at that. This is certainly some sort of masterpiece; I understand it, but I don’t want it.

One last thought — I spent most of the first half wondering who Laydu absolutely reminded me of, until I got it… oh wow, young Johnny Cash! Not the voice, but the face, at times. Check out this picture and tell me I’m wrong!

I have the same feeling about a lot of the films of the later New Wave directors. First, a lot of what they did was theoretical and not really up on the screen. Second, what they did innovate was so quickly followed by others that it's hard to appreciate them for doing it. Also, many of the films tell stories of people I just don't like. Two examples: Breathless (1960) and Jules and Jim (1962). Not that there aren't films by both men I admire -- especially Godard!

I did really like Bresson's film Pickpocket. I'm gonna guess that you will get it a C... Plus!

A big reason I love Calvary is that Father James is a decidedly complicated character. The fact that he abandoned his troubled daughter to join the priesthood is very important. He is flawed. Of course, I love Pasolini's The Gospel According to St Matthew, so who knows...